Winnebago Villages and Chieftains of the Lower Rock River Region

by Dr. Norton William Jipson

|

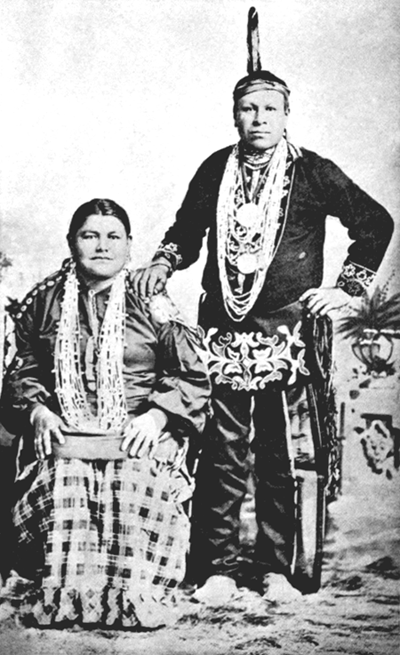

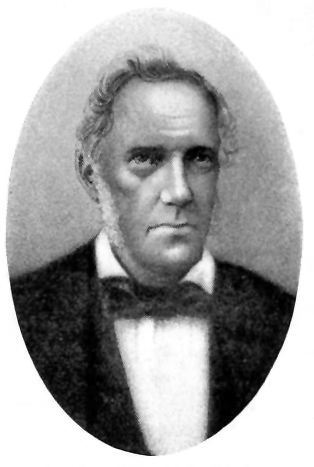

| Young Winneshiek and His Wife |

(125) In the Seventeenth Century, the Winnebago Indians were discovered by the Jesuit missionaries on Lake Winnebago, and their traditions say their original home was on the so-called Red Banks, on the border of Green Bay.

At an early day, they found their way along the Fox and Wisconsin rivers, where they established villages, and eventually along the Rock River and its tributaries, including the Four Lakes.

They were said to have emigrated southward along the Rock River in 1728, and in 1742 one-half of the tribal members were said to be on Green Bay and the other half on Riviere la Roche (W. H. C. XVII-400), and, in 1777, they were said to have a village "two leagues from the Mississippi on a small stream called La Roch," (same XVIII-366).

Winnebago tradition places their Rock River residence at a very early date. Chief White Breast, who, in 1829, had two villages on Sugar River, told his grandson, Ely Rasdell, that both his father and grandfather resided on Lake Koshkonong, on Rock River, which, certainly, would make their removal to that point sometime previous to the end of the Eighteenth Century.

The treaty of 1825 recognized the Winnebago title to the territory containing the mines which were the richest in lead ore. The boundary line was on the ridge separating the tributaries of the Rock from those of the Mississippi River, and the Rock River formed the eastern boundary of the Winnebago country.

(126) That the Winnebago loved the Rock River is a matter of common knowledge. Its waters were well stocked with fish, water fowl of various species were plentiful, fur bearing animals dwelt along its shores.

In 1824, Thomas Forsyth, Indian Agent at Fort Armstrong, (Rock Island), wrote: "On Rocky River there are twelve or fourteen Winnebago villages. The principal one is called Cash-co-nong, and lies about forty-five miles west from Millwakee on Lake Michigan. On both sides of Rocky River, the land is low and full of marshes and sands, and makes it very disagreeable to travel by land; particularly after the first ninety miles from the mouth of Rocky River. Indeed, it is one continual swamp, marsh, and pond to its source, and all the travelling is done by means of canoes."

In 1825, we are told by Maximilian. Prince of Weid, "on Rock River, the Indians caught 130,000 muskrats." The next year's catch was about half that number. Within two years afterward the muskrat was nearly exterminated on the Rock River field." (Steven's St. Louis.)

Although varying with the seasons, the prices which the Indians received for muskrat skins, during the years from 1800 to 1832, averaged from 22 to 25 cents each. At various times, traders were licensed to deal with the Indians at Grand Detour, which appears to have been an especially desirable point, and at various points along the river.

For various reasons, we will consider Koshkonong the farthest north of the Lower Rock River Winnebago villages, and will begin with that village and attempt to give a sketch of each village in rotation as we proceed down the Rock River.

That, at a very early date, Koshkonong was an important point and a gathering place for the Winnebago is well attested. We have given Thomas Forsyth's statement, made in 1824, and proving the importance and size of this village. The same year, Major Henry B. Brevoort, Indian Agent at Green Bay, gave the number of Winnebago at Kuskawoinanque as two hundred, and he calls this village "great village of the Winnebago." If this evidence is considered insufficient, we have other proof. After the Winnebago disturbance of 1827, the white settlers of Northern Illinois and Southern Wisconsin feared another outbreak and Alexander Wolcott, Indian Agent at Chicago, (127) wrote to the Secretary of War concerning the attitude of the Winnebago, and urged the reinforcement of the Fort Dearborn garrison, for, said he: "Should hostilities be commenced and this post left ungarrisoned, this settlement must necessarily be abandoned. It is but eighty miles distant from Koshkonong the gathering place of the Rock River Indians (italics ours) and can be reached by them in two days," (20th Cong. Doc. No. 277.)

Winnebago tradition asserts that Koshkonong was their important Rock River village, and Ely Rasdell, whose father, Abel Rasdell, married a daughter of Chief White Breast, noted Rock River Chieftain, informs us that it was an important point. He also says that White Breast's father was called Kee-zuntshga [Kizų́cka], meaning soft-shelled turtle, and his grandfather was called Ma-sho-pa-ka [Mącopaga], meaning grizzly bear head. Both lived at Koshkonong and Soft Shelled Turtle was a physician. He was said to have been possessed of such professional skill that all of his patients recovered, and there was no graveyard at Koshkonong.

In 1829, the famous chieftain, White Crow, presided over this village, and that year he was visited by the noted Potawatomi chieftain, Shaubena, who, as a trusted messenger, asked him if he intended to participate in the premeditated hostile Indian movement against the whites. In 1829, John H. Kinzie, in his official list of Winnebago villages and chieftains, gave the population of Koshkonong as fifty-seven. It had dwindled from the two hundred as given by Brevoort in 1824.

As I will shortly explain, there are reasons for believing that the popularity and great personal following of White Crow had much to do with the large population of Koshkonong. In the first mentioned year, Morah-tshay-kaw [Moracéga], the Traveller, otherwise known at Little Priest, became the head chieftain. His son, also called Little Priest, whose prowess as an aid of the United States Government in the war upon the Sioux Indians has often been described, was born and raised at Koshkonong.

During the Black Hawk war, Oliver Armel, a Frenchman married to a Winnebago woman, was sent by General Henry Dodge to learn the intentions of the Winnebago at Koshkonong. He reported them as living in a state of fear bordering on terror and so nearly starved that they were living on grass and roots. At this time, some of the Indians were determined to kill Armel, (128) saying that all white men, whether French, English, or American, looked alike to them, and they were determined to kill all who wore hats. He was saved by White Crow.

In passing, it may he well to discuss the derivation of the word Koshkonong. It is not a Winnebago derivative. The Winnebago always speak of it as Day (or Tay)-ma-ha [Te Mąhá], or Mud Lake. As to the word Koshkonong, after considering the various explanations of its origin, the Rev. E. P. Wheeler, an unquestioned authority on Algonquin place names, discarding such words as, "The Lake We Live On," "A Frightful Place," "The Place Where He Got Away." etc., says that the explanation given by the old Beloit trader, Thiebeau, is probably the best. The Algonquin for the place of shaving is "Kosh-ke-bah-zo-nong." If we allow for the usual shortening of Indian by dropping their middle syllables, we have Kosh-ke-nong.

Passing along toward the mouth of Rock River, we next reach Catfish Village, which Kinzie tells us, had two lodges and thirty-eight inhabitants. The exact location of this village is unknown to me, but it was probably near the mouth of the Catfish River. Round Rock Village, said by Dr. Lyman S. Draper to have been the village at the site of the present city of Janesville, had two lodges and thirty-one people, presided over by Little Chief. The Winnebago name for this village is E-nee-poro-poro [Įnį́poroporo, "Round Rock"].

Farther along, and, according to Kinzie's figures, only a short distance from Turtle Village, we find Standing Post Village, with one lodge and seventeen people, ruled by Coming Lightning.

Now we arrive at Turtle Village on Turtle Creek, which the Winnebago called Ke-chunk-nee-shun-nuk-ra [Kecą́k Nįšąnągᵋra]. In 1822 Thomas Forsyth, writing to Governor Cass, in relation to Indian hostilities toward the lead miners at Galena, said: ''In my opinion. nothing is to be apprehended from any of the Indians in my agency (Fort Armstrong), but I cannot say as much for the Winnebago who have a village about sixty or seventy miles east of the lead mines on a branch which falls into the northern fork of Rocky River and is called Paystalon." While Forsyth's statement is not perfectly clear, he must have meant Turtle Village. The northern fork of the Rock River must be the branch which starts the farthest north. He could hardly have (129) meant the mouth of Sugar Creek; as Keating, describing Major Long's visit to that locality in 1823 tells us of the mixed tribes of Indians living there but does not speak of a large Winnebago village. Undoubtedly, at that time Turtle Village was second in population to Koshkonong. The proof of that statement has already been given. However, in 1829, Kinzie's list (p. 49) gives Turtle Village a population of six hundred Winnebago occupying thirty-five lodges, while the population of Koshkonong had dropped from the two hundred assigned to it by Kinzie to fifty seven people.

White Crow the diplomatic genius and born leader of the Winnebago, now presided over this village. Many aspersions, most or all of which are entirely unwarranted, have been cast at the memory of this chieftain. He was said to have been present at the Council of the Four Lakes called to ascertain the disposition of the Winnebago Indians during the Black Hawk War, and, on that occasion, to have used his influence in a manner derogatory to the whites, but the official report of that meeting shows that he was not present. After he had secured the Hall girls from the Potawatomi, who held them subsequent to their capture in the Black Hawk War, and delivered them safe and sound to the whites, General Dodge said to him, "Your treatment of the girls was, as admitted by the girls themselves, noble, kind, and humane. No man, either civilized or savage could have acted with more delicacy of feeling that you have done on this occasion." The statement he is said to have made on the aforesaid occasion, derogatory to the white soldiers, and his subsequent arrest is offset by a letter of Henry Gratiot's stating that the arrest was unwarranted and the result of popular clamor, which leads to the conclusion that he did not make the disparaging remarks. The statement that he attempted to lead the white army into a trap was based wholly on the hysterical fears of the white settlers that something of the kind was about to happen. There is not sufficient time for a full discussion of this subject; suffice it to say that after an extensive search of the official Indian records, I can find no documentary evidence to prove that White Crow was anything but a loyal friend to the white man, and I am convinced that, in common with Shaubena, the well-known Potawatomi chieftain, the memory of White Crow should be cherished as a true friend (130) of the pioneer settlers with whom he came in contact. At the Prairie du Chien Council of 1828, White Crow was the chief orator for the Winnebago. In one of his speeches he made this assertion to Governor Cass: "Father! Since I have known good from evil, no white man can say I have done him harm. I speak before the Great Spirit who knows what I say. I hold you fast by the hand." He prefaced one of his speeches by the following remarks to Governor Cass: "Father! You who are before us, we look upon as we do the Great Spirit. He has placed a pen in your hand; he has made your skin white. But he has made us red, poor, and objects of pity."

At the annuity payment of 1832, held at Fort Winnebago, Governor Porter asked the Winnebago to deliver to the white army those of their number who had assisted the Sank and Fox in the Black Hawk War. He accused them of various acts of dishonesty, such as lying and stealing provisions from the settlers. Replying, among other statements, White Crow naively said: "We thought it was only us who were foolish and could tell lies; but I find that some of you whites are as good at it as many of our young men. Many of the whites are as bad as we are. They took our corn and many articles as they passed our villages, and have even taken up the dead that were buried and took off their blankets, etc., in which they were wrapped." (23d Cong. Indian Removals, IV.)

That White Crow was not an hereditary chieftain, but by sheer force of personality and merit became the chief spokesman of the Winnebago. may indicate the reason why Turtle Village had a large population in 1829, while the population of Koshkonong had diminished; simply showing the large personal following of people who desired him to be with their chieftain.

During the Black Hawk War, although Kinzie's annuity list shows him to have been living at Turtle Village, White Crow was not the principal chieftain. Perhaps the duties incident to his tribal leadership had caused him to resign as village chieftain. Under date of December 22, 1832, Henry Gratiot, sub-Indian agent writing to Governor Cass, designated Whirling Thunder as head chief of Turtle Village. Whirling Thunder was said to be a man of great reputation for sagacity and wisdom in council. At the close of the Black Hawk War, Whirling Thunder, with a large band of his Rock River followers, (131) went to Iowa county, Wisconsin. A letter from Henry Dodge, Indian Agent, to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, stated he was there with a relative, John Dougherty, a white trader, formerly of "Old Sugar River Digging," who had married a near relative of Whirling Thunder. Whirling Thunder lived to an advanced age and died in Nebraska.

Before considering the Winnebago villages which are known to have existed farther down the Rock River, it may be well to consider those at the lower Pecatonica and its tributary, the Sugar. In 1823, Major Long, travelling up the Rock River from Kishwaukee, reached a small stream called the “Pektanons, a diminutive of Pektanon, a neighboring stream into which it discharges itself a few miles below.” The Indian Village, situated on the main stream, consisted of seven permanent and three temporary lodges, inhabited principally by the Sauk, Fox, Winnebago, Menomini and Potawatomi. Their chief was a Sauk, and his name was Wabetega. (Keating, p. 180.)

The region about the mouth of the Pecatonica became a noted gathering place of the Rock River Winnebago. The well-known trader, Stephen Mack, lived and had his place of business at Bird's Grove, which was close by. In 1829, Mack married a half-breed Winnebago woman, daughter of the Blacksmith, a Winnebago who lived at the Four Lakes. While it has been stated that Mack's refusal to sell liquor and firearms to the Indians, was productive of ill-feeling, there is evidence that his place was much frequented by the Winnebago and Potawatomi, and his influence over the Indians frequently prevented the shedding of blood.

In 1831, Henry Gratiot, writing to William Clark, Superintendent of Indian Affairs, suggested paying the Winnebago annuities at the mouth of the “Pe-ke-tol-e-ke.” "There," he says, "they hold their councils and from there they start on their winter hunt. Their women and children could go up in their canoes and take care, at least, of their own share of the salt and money." This letter was in the nature of a protest at the drunkenness and profligacy noticed among the Winnebago whose annuities were paid at Fort Winnebago, and it brought a hot retort from John H. Kinzie, agent at the Fort, who charged Henry Gratiot with trying to prejudice the Indians (132) against the agency at Fort Winnebago, and having the annuities paid at a point near the trading house in which Colonel Gratiot had a financial interest. Kinzie denied the statement that the Rock River Winnebago were in the habit of holding their autumn meeting at the mouth of the Pe-ke-tol-e-ke, preparatory to starting on their winter hunt, saying it was only the lower Rock River Winnebago who thus met.

Thanks to the affidavit of James P. Dixon, we shall be able to state the location of the Winnebago winter hunting grounds. While Henry Gratiot's agency headquarters are said to have been at Gratiot's Grove, in his correspondence he frequently mentioned his "agency at the Mouth of Sugar Creek." (See also letter of D. M. Parkinson in the Mineral Point paper. Miner's Free Press, September 15, 1840.)

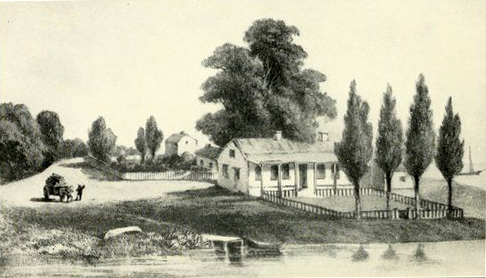

Thus we can infer that the mouth of the Pecatonica and the neighboring region, including the mouth of Sugar River, at one time constituted an important rendezvous for the Winnebago. While the mouth of the Pecatonica and region round about was important as the gathering place of the Winnebago, Kinzie mentions only one Winnebago village at the mouth of the Sugar, and that a small one presided over by Mounk-ska-ka [Mą́kskaga], or White Breast. This village contained one lodge of twenty-three people. Farther up the Sugar was another of White Breast's villages containing nine lodges and one hundred and sixty-seven people. This village was at about the location of the present city of Brodhead. Curiously enough, the Winnebago name of this village, Na-hoo-rah-roo-hah-rah [Nąhųra Rohara], means sturgeon's spawn. During the Black Hawk War, White Breast is said to have acted as a scout for the American army. Something of his biography has been given. He was with his tribe in the Blue Earth Country and died just before they left Mankato for Usher's Landing, Dakota. White Breast's daughter married Abel Rasdell, a white settler of the Four Lakes country, and a son, Mr. Ely Rasdell, is now living in Winnebago, Nebraska.

There was one well-known chieftain who resided on the banks of the Pecatonica near the site of the present city of Freeport. Concerning this chief and his family relationship, authorities have been confused. The Elder Winneshiek, who presided over the Pecatonica village, was called by his people, Ma-wa-ra-ga [Mąwáruga],

|

| 132 verso |

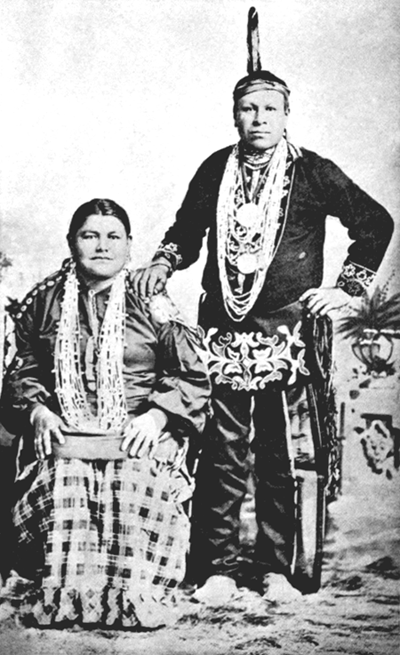

| Winneshiek (Wakon-ja-ko-ga) In center of group Plate I |

(133) meaning muddy. The name Winneshiek is an Algonquin equivalent of the Winnebago name Ma-wa-ra-ga. Winne means dirty or brackish as applied to water, and shiek (properly zick) means a growth. This name is frequently applied to the yellow birch tree, as the bark of this tree has a dirty or smoky color. (Rev. E. P. Wheeler.) As applied to Winneshiek, this name undoubtedly refers to the beard which was an hereditary characteristic of the male members of the Winneshiek family, having been possessed by the elder Winneshiek, his son, Coming Thunder, and grandson, John Winneshiek, of Black River Falls, Wisconsin.

John Blackhawk, a grandson of Chief Coming Thunder, says there is an admixture of white blood in the Winneshiek family, which was related to the well-known French Winnebago Decora family, and he thus accounts for the existence of the beard in the various members of his family. The elder member of the family, Ma-wa-ra-ga, is said by his descendants to have been born on Doty Island in 1777. His son, Coming Thunder, was born at Portage about the year 1812. The elder Winneshiek became very bitter toward the whites. This attitude was due to the fact that the white miners trespassed on the mining lands, title to which had been given the Winnebago by the treaty of 1825.

Previous to the so-called Winnebago war of 1827, Winneshiek met John Connolly, Indian Agent at Galena, complained bitterly of the duplicity of the whites, and uttered what, in the light of subsequent developments was considered an ominous threat against the white settlers. Undoubtedly his hatred was augmented by the fact that his son, Coming Thunder, was captured at his Pecatonica village by the white army under Colonel Dodge and held for some time as a hostage.

While the prevalent opinion gives White Cloud, the so-called Winnebago Prophet, credit for Winneshiek's participation in the Black Hawk War on the side of the Sac and Fox, there are reasons for believing that Winneshiek's hatred for the whites prompted him to persuade White Cloud to join Black Hawk in a desperate effort to force the whites off from the land claimed by the Indians.

As there has been some misunderstanding, let it be distinctly understood that Winneshiek the younger, otherwise called (134) Wan-kon-ja-ko-ga [Wakąjaguga], or Coming Thunder, was the man who, in Minnesota, was made head chief of the Winnebago by order of the United States government, and that the elder Winneshiek left the Pecatonica region soon after or during the war of 1827, and died in 1835 near Hokah, Minnesota.

Notes on Stephenson county, Illinois, by William J. Johnston [p. 242]. a copy of which can be found in the Chicago Historical Library, tell us the lodge poles and other equipment which marked the site of Winneshiek's village were in evidence when the first white settlers located at the site of the present city of Freeport.

Coming Thunder was a man who stood very high with his own people, as well as with his white acquaintances. As it does not properly belong here, I will not attempt to give a sketch of his last years in Minnesota, his removal to Usher's Landing in Dakota, his flight down the Missouri River, and his death in 1864 among the Iowa Indians in northeastern Kansas. He was a man of much natural ability, but his treatment by the whites made him an agnostic concerning the white man's religion and institutions. He was always a so-called blanket Indian, and did not take kindly to the customs of the white man. Much more could be said about the Winneshieks, but the short space allotted for this paper forbids.

Returning to the main branch of the Rock River, we continue our course down stream. At Kishwaukee, we find Sycamore village, with (in 1829, Kinzie) three lodges and forty-eight people. As early as 1814, Thomas Forsyth, in a letter spoke of the Potawatomi, Menomini and Winnebago as residing in the neighborhood of the Cottonwood River, meaning the Kishwaukee; and James P. Dixon, in an affidavit, speaks of the village at the mouth of the Kishwaukee River, about thirty five miles up the Rock River from Dixon.

The next point which we will consider is Grand Detour. It was the opinion of my friend, the late William D. Barge, a man who was familiar with many details of Northern Illinois history, that a Winnebago village had existed at Grand Detour. This opinion was based on the statements of early Grand Detour settlers that, in an early day, the evidence of a former Indian village could be seen, just inside the river bend at that point. The statement contained in Henry Gratiot's journal of April 17, 1832 (I. O. F.) tells us that in company with twenty-six (135) Winnebago he "descended the Rock River" (from Turtle Village) "fifty miles, to Zharros Village * * * descended sixty miles to Ogees Ferry" (Dixon) "descended the river forty or fifty miles to the Prophet's Village." Chief Jarro was one of John Dixon's steady customers, and his village could not have been far away. Certainly, there is presumptive evidence that Jarro 's village was at Grand Detour, although the affidavit of James P. Dixon fails to record that fact:

That the trading house of the old French employee of the American Fur Company, La Sallier, was located at Grand Detour seems to be an assumed fact. William D. Barge notes the fact in his “Early Lee County” and gives proof of the existence of this trading house, and also of the discovery of its remains, decaying logs, cellar, etc., by Joseph Crawford in 1835. In my investigations I unearthed information showing conclusively that the noted Winnebago chieftain, Baptiste La Sallier, who became head chief of the tribe by order of the United States government, after the removal of Winneshiek in 1859, was a grandson of the old French trader. This fact is attested by several of the descendants, who are now living in Nebraska. Baptiste La Sallier is known to have spent his early years at Turtle Village. An affidavit states that he was a brother of Mrs. Joseph Thibeau. He was the son of Joseph La Sallier and a Winnebago woman, while Joseph La Sallier was the son of the old trader, Pierre, or St. Pierre La Sallier.

Arriving at the city of Dixon, but reserving for the last portion of his paper a consideration of John Dixon and his relations, with the Winnebago, we will briefly notice the Prophet's Village, called by Kinzie, Sugar Camp, and the so-called Winnebago Prophet—White Sky, White Cloud, Fair Sky being some of the names by which he was known to the early Indian officials. In 1829, Kinzie gives the village a population of ninety-eight with six lodges. James P. Dixon (in his affidavit) states that in the winter of 1832 he stayed in the Prophet's village two days and one night. His estimate of the population was about one hundred warriors, making the number of villagers between three and four hundred. He says he did not stay at the village, but about four or five miles below at their hunting ground.

(136) The population of the Prophet's village was made up of half-breed and mongrel Winnebago, with a liberal admixture of other half-breed Indians. That the Indians at Prophet's village were by the Winnebago considered a bad lot, is evidenced by a letter from General Joseph M. Street, Indian Agent at Prairie du Chien, to General William Clark, Superintendent of Indian Affairs at St. Louis, under date of July 6, 1831. He said: "The Winnebago now desire me to ask their Great Father to break up this town on Rock River, as they are apprehensive that renegade Winnebago, with other bad Indians, may do mischief, and the whole Winnebago nation have to suffer for it." On July 7, 1831, John Reynolds, Governor of Illinois, wrote to the Secretary of War. "There is a village of bad Indians on Rock River about thirty miles from its mouth which I will recommend you to have moved to the west side of the river. This may save a great deal of trouble." (20th Cong. 1st Sess., II. H. Doc. 117.) To a certain extent, the lower end of Rock River appears to have been a melting pot for various tribes of Indians. Prior to 1823, it is doubtful if there were any villages of pure blooded Winnebago below Turtle Village. As we have seen, both Forsyth and Keating tell us that Kishwaukee village was made up of Indians of various tribes, and Keating makes the definite statement that the Pecatonica Indians were a mixture of Potawatomi, Sac, Fox, Menomini, Winnebago, etc.

Reverting to the Winnebago Prophet, we cannot attempt to give the various opinions regarding the Prophet's character. It is interesting to note that after the Black Hawk War, he allied himself with the Winnebago, and probably died while his tribe was living in the Blue Earth country of Minnesota. One son, called the Young Prophet, succeeded his father as chieftain.

A paper on the subject of the Lower Rock River Winnebago would be far from complete without a discussion of John Dixon's relations with the Winnebago. It is a matter of common knowledge that John Dixon, founder of the city of Dixon, was the successor to Joseph Ogee in the ownership and management of the ferry which was maintained for the benefit of travelers who desired to cross the river on their journey from Peoria to Galena.

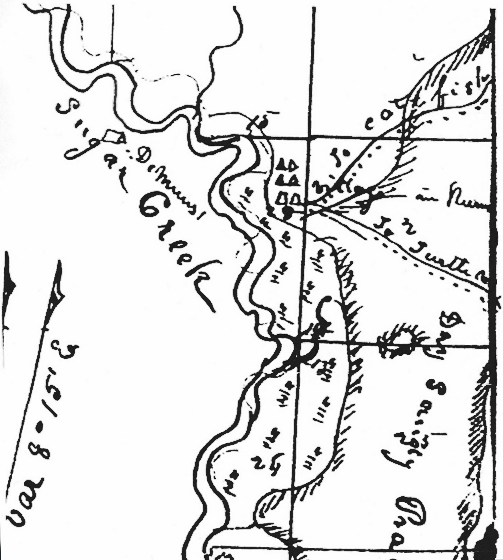

(137) At that point, Mr. Dixon maintained a general store, and an affidavit of his son, James P. Dixon, to which we have already alluded, made in 1838, shows that his dealing with the Indians was more extensive than was formerly believed. This affidavit, made in support of John Dixon 's claim for $2,298.25, for merchandise sold to the Indians and allowed him under the treaty of 1837, which provided for payment of the just debts of the Winnebago Indians, gives some interesting facts relating to the extent of Mr. Dixon's trade with the Winnebago. The goods were purchased from Mr. Soulard of Galena, from Henry Gratiot of Gratiot's Grove, and from Julius DeMunn, who had a trading house on Sugar River in the Territory of Wisconsin. DeMunn's trading house appears to have been located at about the site of the present city of Brodhead and right near White Breast's village, as previously mentioned. De Munn was a near relative of the Choteaus, pioneer French Indian traders of St. Louis, and was a brother-in-law of Henry Gratiot.

The Dixons, father and sons, hauled their goods out into the Winnebago Swamp, which, at that time, according to the affidavit, extended to within about twelve miles of the city of Dixon and lay to the southeast. There were twenty or more Winnebago families camped in the swamp. Their lodges were scattered over a radius of twenty miles and they remained there all winter. We thus learn, the location oft he Winnebago winter hunting grounds, which Henry Gratiot told us the Indians started for from the mouth of the Pecatonica. They were the Winnebago Swamp and the locality about four or five miles below the Prophet's Village.

From my esteemed friend, the late William D. Barge, who was a descendant of John Dixon, I have received many items of information relating to Mr. Dixon's personal and business relations with the Winnebago. The old Dixon account book, still in existence, shows us that Mr. Dixon trusted the white man and the Indian alike, and he told Mr. Barge that the only money he lost by trusting an Indian was one dollar owing for an axe sold to an Indian who was killed on a hunting trip. The account book contains charges against ''Daddy Walker," "Limpy," "Old Quaker," "Sour Eads," "Corngather," "Preacher Long Sober Man," and "Blinkey's Brother." "Plump Face" is charged with "massagran" [mąsákera] (meaning lead), (138) "wa sarah" [waséra] (grease), "my sherry, [mąšira]" "flint stone," and "ohanena" (meaning unknown). "Squirrel Cheeks" bought "oats netega." "Fat Squaw with many beads" owes a balance due on a shirt; "Old Blue Coat's Son" is charged with "wy parisable" [waperesebᵋra] (meaning black cloth). Chief Jarro's name appears often. Allusion has been made to the probable fact of his village having been located at Grand Detour.

Pay-chunka [Pecųka], or Chief Crane, is mentioned, and his brother Blue Coat [Wonąžįcoga]. This chieftain seems to have been in the vicinity of the lower Rock River for a long time. Forsyth's Indian Agency account books (Rock Island) show dealings with him in 1824 and 1825.

The dealings of the early white Indian traders constitute a chapter in American history not at all creditable to the whites. It is a story of reprisals and counter reprisals. The Indians were deceived, cheated, and, worst of all, made irresponsible by whiskey, which the designing white traders sold them.

One of the bright spots in this sordid story is the relation of John Dixon to the Winnebago. Not only did he refuse to sell them whiskey, but under his influence many of them, including Chief Jarro, became active apostles of temperance. In the evening of life, Father Dixon, as he was called, received yearly visits from his old Winnebago friends, who camped near his. house and gave exhibitions of dancing in the village hall. On account of his flowing white locks, they called him Na-chu-sa [Nąsú-są], meaning white hair. In his daily visits to the Indians, they talked over the old days, part of the time using Winnebago and part of the time English, and they laughed and wept alternately as they recalled the events in their lives.

In July, 1876, a band of Winnebago came to visit Mr. Dixon, but they were a week too late to see their old friend Na-chu-sa, who had departed for that land which they conceived to be the abode of the departed Spirits. When they learned of their loss, they were inconsolable, and there was much weeping and lamentation. Without giving their customary exhibition, they departed for their home in Black River Falls.

The treaty of Fort Armstrong compelled the Indians to leave the Rock River, and they were loath to go. Undoubtedly, according to their custom, many a suppliant Winnebago retired far from the haunts of his fellow man, and for days abstained (139) from food, trusting that some favoring spirit would appear to him in a dream and promise him an eventual victory over the whites. That they believed they had received such a promise was evidenced by the statement of Chief "Old Soldier" of Turtle Village, who told Henry Gratiot that they were not pleased with the treaty, and "before we move we will carry our wampum to the neighboring tribes; then we will return again. The Great Spirit is mad with the whites and when they gather again to come against us, He will send a sickness among them that will destroy them and we will remain on Rock River in peace." The same faith in the Great Spirit's willingness to destroy the white man had been expressed by the Shawnee Prophet and many other aboriginal soothsayers. But their Deity was never able to save the Indians from the aggressions of the white man.

On February 8, 1833, Henry Gratiot reported that a part of the Rock River Winnebago were in the vicinity of the "Agency, Waters of Sugar Creek,'' and there were many complaints from the white inhabitants of thefts committed by the Indians. They had killed a number of hogs belonging to farmers along the Pecatonica, and he was having much difficulty in preventing hostilities on the part of the whites. (23d Cong. 1833-4. Indian Removals.) In 1835, E. A. Brush, who was sent to induce the Winnebago to move, writing from Detroit to Secretary of War Cass, said that Stone Man (another name for White Breast), Little Priest, and White Crow had gone north of the Wisconsin; that there were about 1,000 to 1,200 Winnebago on Kushkanong, Catfish and Sugar Creek, the Pekatoleka and Rock Rivers, "of whom one hundred and fifty were below Dixon's Ferry."

Commentary

|

|

|

| R. A. Lewis | ||

| White Breast (Stone Man) | White Breast's Village, 1832 (Across the Creek from De Munn's Trading Post) |

"Chief White Breast" = "Mą́kskaga" — a War Chief and member of the Bear Clan. He was famous for having led four Warparties without loosing a man. He was a lead scout in the Black Hawk War. His father was named Kee-zuntsh-ga [Kizų́cka], "Soft-Shelled Turtle," and had a village at Lake Koshkonong. Kizų́cka's father was Ma-sho-pa-ka [Mącopaga], meaning "Grizzly Bear Head." White Breast had a brother called Na-xee-zheb-ga [perhaps, Naxi, "Fourth Born," and Sepka, "Black"]. White Breast's wife was named Hopink-ah [Hopįga, "Good Voice"], and at least two daughters, Onck-say-onc-ah [probably for Haksagā, "Third Born Female"], and No-waw-chock-wink-ah [Nąwácakwįka, "Fortress Woman"]. His first son was named, Mau-na-suntsh-ga [Mąnąksųcka], "Shakes the Earth by the Force of His Step"; his second son bore the name, Shounk-mau-no-nee-ga [Šųgᵋmąnųnįga], "Lost Dog" (probably a nickname); his third son was called, Mau-chgoo-[w]a-shiste-ga [Mącguwąšiška], "Breaks the Band [Bow] with the Force of His Feet." The male names seem to be those found in the Bear Clan, which does not supply village chiefs, but in this case we may conclude that he was the War Chief of the villages named. In 1829, he had two villages, one as shown above on Sugar Creek where the town of Brodhead is now located (42.618540, -89.376291), and a second at the mouth of the Sugar River. The former village was called, Na-hoo-rah-roo-hah-rah [Nąhų́ra Ruhara], "Sturgeon Spawn." Later, in 1835, with Little Priest, he had a village on the Wisconsin River. Both of his daughters married Abel Rasdall. The photograph of White Breast was made by R. A. Lewis in 1865, when a number of Hocąk chiefs had traveled east for treaty negotiations.1

"Thomas Forsyth" — born in 1771 in Detroit, which at the time was a western outpost. By 1798, he had already established himself as a fur trader among the Indians west of the Mississippi. In 1802, he teamed up with John Kinzie to establish a trading post in what is now Chicago. During the Peoria War, he served as a spy for the governor of the territory. During the War of 1812, he acted as an Indian agent, and succeeded in keeping some bands of the Potawatomi neutral during the conflict. He was instrumental in gaining the release of the prisoners held by the Potawatomi after the Ft. Dearborn Massacre. In the 1820's, he served as Indian subagent for the Sauk and Fox at Rock Island, Illinois. He died in St. Louis in 1833.2

|

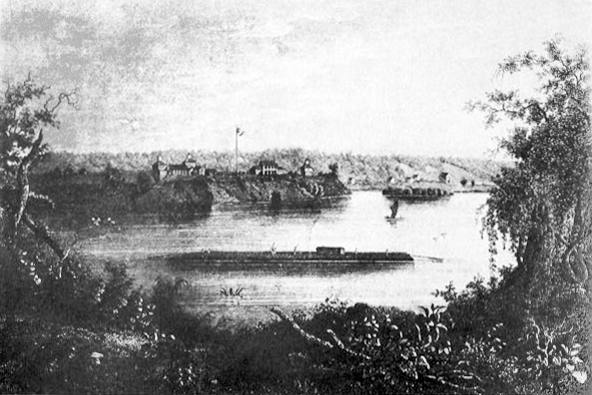

| Fort Armstrong, Showing the Residence of Col. Davenport |

"Ft. Armstrong" — "As this celebrated fort was built on Rock Island, it will be proper to precede our account of it by a brief description of the Island itself. Rock Island is situated in the Mississippi River, opposite the upper end of the city of Rock Island, and between it and Davenport on the Iowa side. It is about two and a half miles long by three-fourths of a mile wide, and contains an area of about a thousand acres. The base of this island is a mass of limestone of the Hamilton group which underlies this section of country. At its lower extremity this rocky exposure rises in an almost perpendicular wall to a considerable height above the water, and was the cause of its being called by its appropriate name — Rock Island. ... After Fort Armstrong was built on the lower point of this island, the view on ascending the river became still more picturesque; and it has been described as one of the most beautiful and romantic scenes in the whole western country. ... In 1816, Fort Armstrong was built on the lower point of Rock Island. The force of regulars under Col. William Lawrence, which came up the river for the purpose of locating and erecting the fort, arrived at the mouth of Rock River and examined the country for a suitable site. They decided on the above location. On the 10th of May, 1816, they landed on the island, and as soon as they had completed their encampment, Colonel Lawrence employed the soldiers to cut logs and build store-houses for their provisions. He also had a bake-house and oven erected, which was the first building finished on the island. The erection of the fort and its accompanying buildings soon followed, and was named Fort Armstrong, in honor of the Secretary of War. It was a substantial structure of hewed logs, built in the form of a square, whose sides were four hundred feet in length. A block-house was built at each of the four angles, and embrazures for cannon and loop-holes for musketry were provided. A magazine store house barracks, and officers’ quarters were erected within the enclosure, and sections of heavy stone work built for protection against fire."3

"25 cents" — the Hocągara called the quarter dollar a "muskrat."

The following locales are shown on this map (generally north to south):

|

|

|

||||

| The Rock River Area |

"Major Henry B. Brevoort" — born in 1775 in an old Dutch family of New York, was appointed as a Second Lieutenant in the U. S. Army in 1801. He distinguished himself at the Battle of Maguago against the British and Tecumseh in the War of 1812. Under the command of Commodore Perry, he was given command of the Marines. He was able to ascertain the strength of the British forces opposing Perry and was instrumental in the American victory in the Battle of Lake Eire. The Commodore's report stated, "Captain Brevoort, of the army, who acted as a volunteer in the capacity of a marine officer on board that vessel [the Niagara], is an excellent and brave officer and with his musketry did great execution." For his conduct in this affair, he was awarded a silver medal. He was promoted to Major in 1814. After serving as a land registrar in Detroit, he was made Indian Agent at Green Bay. He died in Detroit in 1858.4

|

|

| Doctor Walcott |

"Alexander Wolcott" — (1790-1830), a figure in the history of Chicago, related by marriage to the Kinzies. Currie says this about him:5

Dr. Alexander Wolcott was Indian agent at Chicago from 1820 until his death in 1830. He was a Yale graduate, and had come to Chicago from Connecticut. He was appointed physician of Governor Cass western expedition in 1820, one of the party with Schoolcraft, Trowbridge, and John H. Kinzie. Of the Chicago of Dr. Wolcott's day, Schoolcraft tells us: "We found four or five families living here, the principal of which were those of Mr. John Kinzie, Dr. A. Wolcott, J. B. Bobian [Beaubien] and Mrs. J. Crafts, the latter living a short distance up the river." He writes later of continuing their journey: "Dr. Wolcott, being the US Agent for this tribe [Pottawattomies], found himself at home here, and constitutes no further a member of the expedition." There the exploring party left Dr. Wolcott, "whose manners, judgment, and intelligence had commanded our respect during the journey. While his predecessor, Jouett, was Indian Agent, the latter had begun the building of an agency house north of the river, on the southwest corner of the present intersection of North State and North Water Streets. This was later finished by Dr. Wolcott and occupied by him from 1820 to 1823, and again from 1828 until his death in 1830. The building was called Cobweb Castle, perhaps owing to its bachelor housekeeping. In 1823, he was married to Ellen Marion Kinzie, daughter of John Kinzie. Earlier in the same year, when the troops were removed from Fort Dearborn, Dr. Wolcott having been put in charge of the post and its property, moved into one of the officers dwellings. There he lived during the vacancy of the fort until 1828, when he returned to his own house, where he died in 1830. In mourning the death of Dr. Wolcott, Mrs. Kinzie says: "That noble heart, so full of warm and kindly affections, had ceased to beat, and sad and desolate, indeed, were those who had so loved and honored him."6

"Abel Rasdel [Rasdall]" — also called "Abraham," was a trader and spoke fluent Hocąk. He actually married two of White Breast's daughters in succession. These two daughters were Onck-say-onc-ah [probably for Haksagā, "Third Born Female"], and No-waw-chock-wink-ah [Nąwácakwįka, "Fortress Woman"]. His first wife, whom he married in 1834, died; so he married Nąwácakwįka in 1837. The latter's birth order name was Wīhą́gā, "Second Born Female."7

"White Crow" — Kau-ray-kaw-saw-kaw would seem to correspond to Karekasaga, which is unattested and is probably a corrupted form of the name. His name given elsewhere as Kau-kish-ka-ka8 better approximates the expected Kaǧískága, which means "White Crow." He was also known by the near synonym Wąhą́skaga, the wąhą́ being a smaller variety of crow.9 He was nicknamed "The Blind [in One Eye]," or Le Borgne since he had lost an eye.10 He was chief of a village by Lake Koshkonong of about 1200 people who lived in white cedar bark lodges.11 He was the father of "the Washington Woman," who married Yellow Thunder.12 At the beginning of the Sauk War he believed that the Sauks would vanquish the whites and tried to warn them.

The White Crow had told Capt. Beon Gratiot, that he was friendly towards him as his brother was the Winnebago Indian Agent; that he did not wish to see him killed, and that he had better leave Col. Dodge and go home; that the Sauks and Foxes would kill all the whites; that the whites could not fight, as they were a soft-shelled breed; that when the spear was put to them they would quack like ducks, as the whites had done at Stillman's Defeat; and he proceeded to mimic out, in full Indian style, the spearing and scalping in the Stillman affair; and that all the whites who persisted in marching against the Indians, might expect to be served in the same manner.13

He died in 1836 and is buried near the village of Cross Plains.14

|

|

|

||

| John H. Kinzie | Kinzie House, Chicago, 1804 | Indian Agency House (1832) |

"John H. Kinzie" — John Harris Kinzie (July 7, 1803–June 19, 1865) became one of the earliest settlers of Chicago, when his parents moved there from Detroit in 1804. He had great proficiency in Indian languages, and consequently was selected as personal secretary to Governor Cass of Michigan Territory in 1826. In that same year, he accompanied the Hocągara to Washington. In 1827 he was a participant in the Treaty of Butte des Morts. From 1829-1834, he was the Indian Subagent at Ft. Winnebago. His Indian Agency House near Portage, Wisconsin, was one of the earliest houses built in Wisconsin, and still exists today. He married his wife, Juliette Augusta McGill in 1830. She was the author of the famous Wau-Bun, the Early Day in the Northwest.

|

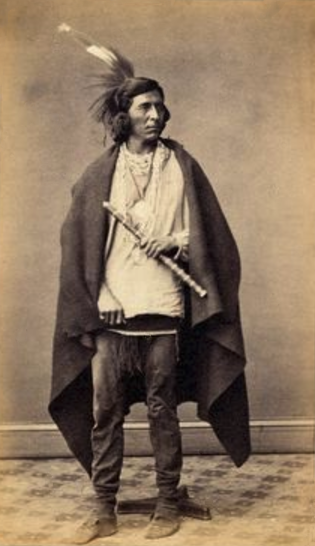

| R. A. Lewis |

| Little Priest (Hųgᵋxų́nųga), 1865 |

"Little Priest" (the Elder) — "Little Prophet," "Little Priest," and "Little Chief," are all common translations of Hųgᵋxųnųga, where strictly speaking, the initial Hųk denotes a chief. The -xųnų- element can mean either "little" or "younger." An individual of this name is shown as a signatory of the treaties of 1828 and of 1832. He also had the clan name Mórajega ("Travels the Earth"), as well as the names Mącosepga ("Black Grizzly") and Rohąt’ehiga ("Kills Many"). He was known to have been of the Bear Clan.15 In a speech on the Winnebago Prophet, Congressman, and Minister to France, Elihu B. Washburne said, "Little Priest was one of the most reputable of all the chiefs, able, discreet, wise, and moderate, and always sincerely friendly to the whites."16 When the Black Hawk War broke out, Col. Gratiot, who was the Winnebago Agent, was ordered by the Army to seek out the Winnebago Prophet in his village at Prophetstown, and to dissuade him from entering the fray. In this endeavor he was accompanied by Little Priest, Broken Shoulder, Whirling Thunder, White Crow, and Little Medicine Man. When they landed at Prophetstown, they were surrounded by hostile men intent upon killing them, but the Winnebago Prophet intervened and gave them his protection. After giving them his personal hospitality for three days, he warned them that his young men were intent upon killing the lot of them, and that they must make a dash for their canoes and make good their escape. This they did, and they were vigorously pursued, but Little Priest and his friends proved stronger, and escaped to Rock Island.17

Horaceka is actually a corruption of Mórajega of much the same meaning. The conversion to Christianity of this Little Priest is related in the Memoirs of Father Mazzuchelli:

While the Priest was preparing to administer the Sacrament of Baptism to a great number of Indians, one of them called “The Little Prophet” cast off the woolen blanket in which he had been wrapped and threw it far away; being asked the motive of this singular behaviour, he answered that thus he desired to show his sincerity, in utterly despoiling himself of all his evil ways and becoming a new man. This was the fruit of the familiar instructions. This Indian had comprehended the true meaning of the change which Faith in Christ should operate in the soul, that is, that change which makes us live by the spirit and die to whatever is carnal and sinful. All Christians are acquainted with this doctrine, but few indeed cast far away the mantle of their vices as did this poor savage.18

The elder Little Priest was eclipsed in fame by his son of the same name, the last war chief of the Hocągara, after whom Little Priest College is named.

|

Little Priest the Younger and Henry Decorah, of Co. A |

"Little Priest" — The name Hųgᵋxų́nųga is from Hųk-xų́nų-ga, where hųk can be translated as "chief, priest, prophet"; and xų́nų as "young, little." These may be recombined to give many different permutations of his name, the two most common being "Little Priest" and "Young Prophet." He was a member of the Bear Clan, and was believed to have been blessed with Grizzly Bear Powers. In the 1840s he succeeded his father (of the same name) to become the last War Chief of the Hocąk nation. He was accused of participating in the Sioux Uprising of 1862, but by 1864 he was with Stufft's Independent Company, Indian Scouts, US Volunteers fighting the Sioux in Sully's Expedition. In 1866, with the Winnebago contingent of the Omaha Scouts, he single-handedly engaged 32 Lakota, taking five scalps, but receiving a wound in the leg that later proved fatal. In Nebraska the tribal college and the annual powwow are named in his honor. Two stories (1, 2) in this collection are about his exploits.

|

| George Catlin |

| General Henry Dodge, 1833 |

"General Henry Dodge" — Henry Dodge was born October 12, 1782 to Israel Dodge, a veteran of the Revolutionary War, and Nancy Hunter. He was the first American child born in the present state of Indiana. Israel Dodge divorced his wife and moved to Missouri, where Henry joined him at age 14. He served under his father as Deputy Sheriff in 1805, and in the following year got involved in the Burr Conspiracy, but upon learning that President Jefferson had declared the conspiracy an act of treason, he immediately renounced his participation. In 1806 he was given a commission in the Missouri Militia, and in 1813, he was appointed U. S. Marshall. With the outbreak of the War of 1812, he fielded a company of mounted Missouri Militia, and during the course of the war, rose to the rank of Major General. In an incident of that war, as recalled by his son Senator Augustus Caesar Dodge,

... the lives of five hundred men, women and children of the Miami tribe, [were] not only spared by [Henry Dodge] after they had become his prisoners, but protected from almost instant death by Colonel Dodge, who threw himself between the Miamis and the muzzles of a hundred and ten cocked rifles in the hands of Capt. Marshall Cooper's company, aimed at the Indians by brave but enraged Missourians, who had given way to the ignoble passion of revenge - the Indians having a short time before murdered a number of their kindred and friends.19

In 1827, he moved to Wisconsin, where he commanded militia during the Winnebago War. In October of that year he established himself at what is now Dodgeville. When the Black Hawk War broke out in 1832, he organized and commanded the Michigan Mounted Volunteers (Wisconsin being then part of Michigan Territory). He distinguished himself at the battles of Horseshoe Bend, Wisconsin Heights, and Bad Axe. He was then commissioned a Major and given command of the U. S. Regiment of Dragoons in 1834. He was made Governor of Wisconsin Territory from 1836 to 1841, and again from 1845 to 1848. At that time, the Territory encompassed the present states of Wisconsin, Minnesota and Iowa. He turned down attempts to nominate him for president on the Whig ticket on account of his loyalty to Martin Van Buren. When Wisconsin became a state, he served two terms as its first U. S. Senator from June 8, 1848, to March 3, 1857. He died in Burlington, Iowa, June 19, 1867.20

|

| Lewis Cass |

"Governor Cass" — Lewis Cass (1782 – 1866) was governor of Michigan territory from 1813-1831. He began his career in the Army, first as a Colonel of Ohio volunteers, then as an officer in the regular U. S. Army, where he rose to the rank of General. James Madison appointed him to be Governor of the Michigan Territory, a post he held for nearly two decades. His tenure saw a great land cession by the native tribes of the region. He left this post to become Secretary of War under President Jackson. He later became Minister to France, Senator from Michigan, Secretary of State (1857-1860), and ran unsuccessfully as the Democratic Party nominee for president against Zack Taylor. He was a long time prominent member of the Masons.21

"Kinzie's list" — this list can be found in its entirety on pages 49-51 of The Search for Ke-Chunk.22

|

| Colonel Henry Gratiot |

"Henry Gratiot" — was born in St. Louis, then under the governance of the Spanish, on April 25, 1789. He was an ardent opponent of slavery, and when Missouri was admitted as a slave state, he moved north to the Galena area in Illinois so that he might live in a Free State. He and his brother purchased from the Hocągara mining rights to the lead deposits for which this region was known. Gratiot developed close personal relationships with the Hocąk nation. During the Winnebago War of 1827, however, he did allow the government to build what they later called "Ft. Gratiot" on his property. In 1830, he was given the post of Subagent to the Hocąk Nation. At the onset of the Black Hawk War in 1832, he was sent as an emissary with Little Priest and other prominent Hocągara to deliver a message from Gen. Atkinson, but they barely escaped with their lives. (For his adventure with Little Priest et alia, see Wau Bun). In 1834, he sold his mining interests and established a farm in the area. Every autumn a band of Hocągara would camp on his land to visit with him and his family. In 1835, the bad condition of the Rock River bands came to his attention, so he undertook successfully to reestablish their annuities from the government. He fell ill while attempting to return to Wisconsin from Washington, and died in Baltimore, April 27, 1836. In Wisconsin, he is remembered in the names of the village of Gratiot, and the town of the same name.23

|

| R. A. Lewis |

| Whirling Thunder |

"Whirling Thunder" — this portrait of Whirling Thunder was made by R. A. Lewis in 1865. His name in Hocąk, Wakąjagiwįxga, actually means "Whirling Thunderbird," and is a clan name in the Thunderbird Clan. He was chief of Turtle Village where Beloit now stands. He was said to be, "a man of real repute for his sagacity and wisdom in council." He died in 1850, but his wife lived to be one-hundred years old, dying ca. 1889. They had a son Mą́zamąnį́ga, "Iron Walker," whose chief claim to fame was that he killed the government translator Pauquette.24

"John Dougherty" — his wife, Mary, was related to Whirling Thunder.25 Whirling Thunder's band occasionally camped on his land, which was near the lead mines in the Sugar Creek area. Mary, John Dougherty's wife, whom he married in 1831 in Galena, was described as a "half-breed," which usually mean half white and half Indian.26 Mary's mother was Kenoko, who was "sister to the principle Chief." The principal chief in question is probably Whirling Thunder. Kenoko's father was Monaka, known in Washington as the "Winnebago General."27 Monaka may be for Mąnąka, "Arrow." In a deposition by a D. G. Fenton, the deponent said of Dougherty, "... he is a man of Truth and veracity and in good repute as a man of honesty and propriety Sobriety and reputed to possess considerable property in said Territory [Wisconsin]."28 His occupation was that of a trader and a smelter of lead in partnership with others. During the Blackhawk War, his buildings were burned to the ground, and all his trading goods were confiscated by either the Sauks or the Hocągara. He and his people had fled, having been warned in a threatening way by the Winnebago Prophet himself, that he was alive only because of his marital connection.29

|

|

| Charles Wilson Peale | |

| Col. Stephen H. Long |

"Major Long" — born in New Hampshire in 1783, he obtained a Master's Degree in 1812, and was commissioned a Lieutenant in the Army Corps of Engineers in 1814. Two years later he was promoted to Major and served under Andrew Jackson in the south. In 1817, he led an expedition to St. Anthony Falls, Minnesota, which ultimately resulted in the construction of Ft. Snelling under his recommendation. In 1819, he explored the Missouri River, and in 1820, the Platte. In 1823, he lead an expedition to explore northern Minnesota and adjacent areas of Canada. In 1826, in pursuit of his career as an engineer, he received patents for various locomotive design components. In 1836, he explored a pathway for a railroad from Maine to Quebec, but the project fell through due to political problems. While working for railroads in Georgia, he was appointed to the newly formed U.S. Corps of Topographical Engineers in 1838. He supported the Union during the Civil War, and was promoted to Colonel in 1861. He died in 1864.30

"Stephen Mack" — born in 1798, he began his career as an Indian trader in his youth, and became the first white settler on the Rock River. He established himself among the Potawatomi near Prophetstown, and married the chief's daughter, Hononega. At one point, they had to flee the Potawatomi because Mack refused to sell them liquor or guns. They found refuge among the Hocągara at Turtle Village. As the region became settled, Hononega, who never adopted white ways, gained high status in the community for her ability to effective use Indian herbal medicine to effect cures (in an age before medicine was a science). Although she had never converted to Christianity, on her death Mack stated that she had been the most Christian woman he had ever met when it came to her conduct. Mack died in 1850.31

|

|

| Charles Wilson Peale | |

| Gov. William Clark |

"William Clark" — this is the William Clark (1770-1838) famous for the Lewis and Clark Expedition. He was a superintendent of Indian affairs, and served as governor of Missouri Territory from 1822 until his death in 1838.

"James P. Dixon" — his father, John Dixon, known to everyone as "Father Dixon," was the first white settler in the town now bearing his name. He bought the house of Mr. Ogee, who was half Indian, in 1830.

Mrs. James P, Dixon was formerly Miss Fannie Reed of Buffalo Grove. She was married to Mother Dixon's oldest son in 1834 and lived on Main street about half a block east of Galena. There—June 30th, 1836—the first white baby in Dixon was born, and little Henrietta Dixon, we may be sure, was an object of great interest to the entire community, for all hastened to pay their respects to the little pioneer.32

We know of one instance in which James Dixon acted as his father's attorney at law.33 His mother, known as "Mother Dixon," was a good friend of the Indians and entertained Black Hawk on more than one occasion.34

"Mąwáruga" — despite the fact that this is a name in the Bear Clan,35 Winneshiek was of the Thunderbird Clan. The name Mąwáruga was, as Jipson subsequently shows, a nickname. Mąwá does mean "muddy"; the -ga is a suffix indicating a personal name. The -ru- is obscure. It might be ru’, which means, "to carry," in which case the name Mąwáruga would mean, "He Carries Mud," which indeed may have been equivalent to Winne-shiek, and have constituted a reference to his having sported a beard.

"Decora family" — descended from the union of Sabrevoir de Carrie and Hąboguwįga, "Glory of the Morning," then acting as chief of the tribe. They were probably married in 1730. For the Decorah family, see Origin of the Decorah Family, and Glory of the Morning.

"John Connolly" — an Indian sub-agent and interpreter for the Fox at Galena from 1824 to 1828, apparently working for Thomas Forsyth, from 1824 to 1828.36 In 1824, Connolly informed Forsyth that unscrupulous traders were supplying the Fox Indians with vast quantities of whiskey and the Indians were even trading their horses for a supply.37 In 1827, when trouble arose with the Hocągara, Connolly had promises from the Fox of warriors to defend the settlement at Prairie du Chien.38

John Connolly (ca. 1791-ca. 1837), a native of Ireland, was the assistant factor at Fort Edwards and then at Fort Armstrong when the government trading post was moved there from Fort Edwards. ... Sometime before 1830 he was employed by the American Fur Company. The date of his death is not known, but by treaty in 1837, funds were allotted to "the children of the late John Connolly."39

He was married to an Indian woman, probably Fox, since his two sons were characterized as "half-breeds."

|

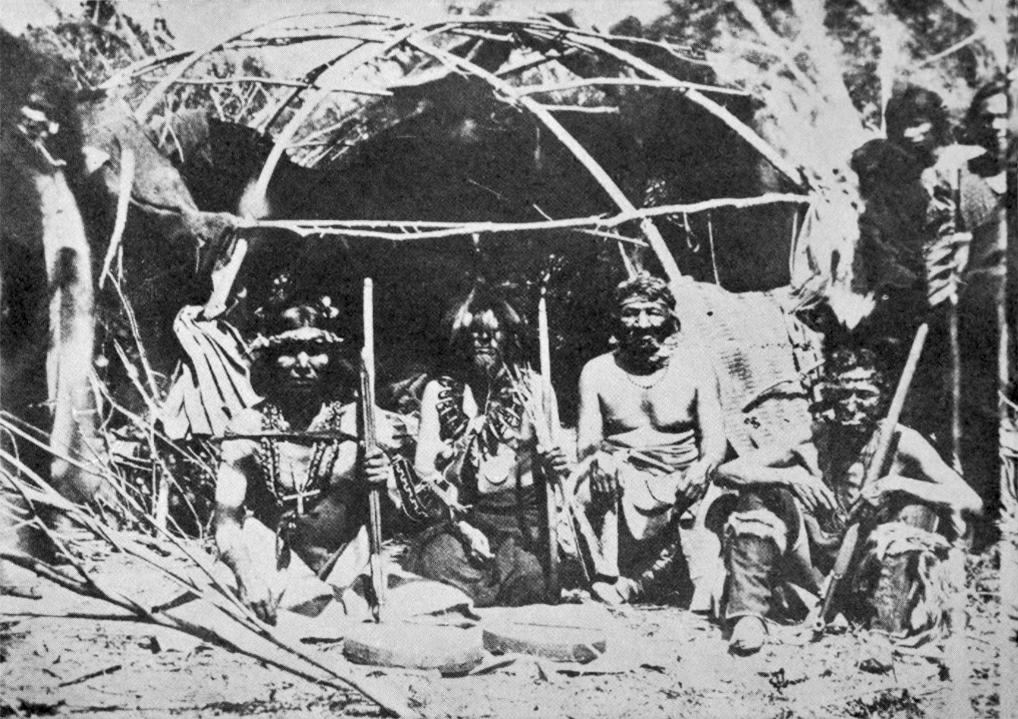

| George Catlin |

| The Winnebago Prophet |

"White Cloud, the so-called Winnebago Prophet" — named "White Cloud" (Mąxisgaga) in Hocąk.

White Cloud, the prophet, was Black Hawk's evil genius. He was a shrewd, crafty Indian, half Winnebago and half Sac, possessing much influence over both nations from his assumption of sacred talents, and was at the head of a Winnebago village some thirty-five miles above the mouth of the Rock. He had many traits of character similar to those possessed by Tecumseh's brother, but in a less degree.40

In conjunction with Black Hawk, the chief of the Sauk, he preached in favor of war against the Long Knives, gaining the support of the Fox, Kickapoo, Potawatomi, and Hocągara. The result was the near annihilation of the Sauks, from which he and Black Hawk barely escaped alive. See also, "A Prophecy."

|

| Coming Thunder |

"Wakąjaguga" — this is a clan name given early in life by the Thunderbird Clan. The real meaning of Wakąja-gu-ga is "Coming Thunderbird." Wakąjaguga was the son of Mąwáruga (see above), with whom he is sometimes confused, since Wakąjaguga is usually referred to as the "Elder Winneshiek," in contradistinction to his little brother, "Young Winneshiek."

"blanket Indian" — these are people who refused to be assimilated into white culture, and therefore tended to dress in blankets rather than button down coats.

"William D. Barge" — the author of Early Lee County, Being Some Chapters in the History of the Early Days in Lee County, Illinois (Chicago: Barnard and Miller, Printers, 1918).

![]()

"Chief Jarro" — Whitney's note on Jarro sums up much of what is known about him:

Jarrot was a Winnebago Indian, perhaps a minor chief, whose village was on the Rock River north of Dixon (Gratiot Journal, April 22, 23, 1832). His Indian name was Owanico, but he was usually called Jarrot or one of its variants — Jahro, Jarot, Jarro, Jerro, Sharro, Zharro. He was given this name for preventing the murder of trader Nicholas Jarrot by a group of unfriendly Indians at a camp near Prairie du Chien just before the outbreak of the War of 1812. The Winnebago Jarrot signed the 1829 treaty.41

Jarro's Hocąk name, here given as Owanico, is probably Howánika, "He Seizes," from howáni, "to take." For the origin of the name Jarro[t], see the story, "Jarrot Gets His Name." The name Jarrot would be transliterated in Hocąk as Žaro[ga].

|

| John Dixon |

"John Dixon" — the father of the James P. Dixon noted above. Whitney's note nicely sums up his life:

John Dixon (1784-1876) came to the Sangamon country in 1820 from New York in the hope that the climate of the West would restore his health. Not only did he recover from the "pulmonary disease" that had seemed imminent when he gave up his clothing business in New York, but he outlived all of his twelve children as well. From Sangamon County, Dixon and his family moved on to Peoria in 1825. There he held numerous county positions — recorder of deeds, circuit clerk, clerk of the county commissioners' court, and justice of the peace. Three years later he moved still farther north to Boyd's Grove in Bureau County, and from Bureau County he went to Ogee's Ferry in 1830. A post office had been established at that place in 1829, and Dixon obtained the position as postmaster soon after his arrival. During his residence in Bureau County, Dixon subcontracted for portions of mail routes and was proprietor of the Galena-Springfield mail stage. In the BHW [Black Hawk War], Dixon served as an assistant to Q. M. [Quartermaster] Enoch C. March and accompanied the 3d Army through part of its expedition across Wisconsin to the Mississippi. After the war he expanded his trading operations and was active in the development of Dixon, which was named in his honor. In 1838 he was elected by the legislature to the state board of public works. Largely through his influence, the U.S. Land Office was moved to Dixon from Galena in 1840. Dixon retired from business some thirty years before his death, but he remained active in civic affairs throughout his life.42

John Dixon died in 1876 at the age of 92, an age seldom attained by anyone of his historical period.

|

| Joel Emmons Whitney |

| Baptiste La Sallier, ca. 1855 |

"La Sallier" — Pierre, or Sainte Pierre, La Sallier is generally recognized as the first white person to have settled in the area. He had been a Canadian voyageur and as early as 1793 settled down to establish a trading post with the Hocągara opposite what is now Grand Detour. He was a guide for the Long expedition of 1823. (For more on Pierre La Sallier, see Webb's Altowan). The Hocągara called Joseph, Pierre's son, Neesgooga [Nįsgúga], "Salt." Joseph La Sallier married a Hocąk woman whose name is given as, Naw-taw-kay-ween-ka, perhaps for Ną́ta’ewįga, "Burnt Tree Woman," a Bird Clan name referencing the striking of a tree by lightning. In addition to Baptiste La Sallier, they also had a son called "Joe Baptiste" and a daughter Wa-xo-pea-nee-win-kaw [Waxopį́nįwįga], meaning "French Woman" (or "Spirit Woman"). Baptiste La Sallier married a Hocąk woman, Na-tchke-tca-xi-win-kaw [Nącgecąk’į́wįga], "Visible Heart," who lived to be 90 years old. Baptiste (ca. 1814-1893) was made co-chief of the whole tribe in association with Winneshiek, and when the latter was deposed, the government recognized Baptiste alone as the head chief.43

|

| Joseph Crawford |

"Joseph Crawford" — born in Pennsylvania in 1811, he was largely self-educated. In 1831 he took up the profession of teaching, but in 1835 bought land near Dixon's Ferry, becoming one of the pioneers of the area. Having learned the science of surveying, he was able to gain extensive employment in the service of local citizens and the government. By 1839 he had risen to the station of County Surveyor, and in 1841 he was elected as one of the County Commissioners of Lee County, Illinois, an office he held for 18 years. He made his fortune in land speculation in Northern Illinois, Iowa, Wisconsin, Minnesota and Nebraska. In 1865, he became president of Lee County National Bank. He was elected in Lee and Whiteside Counties to the Illinois House of Representatives for two terms, during the sessions of 1849-1854. From 1873-1876, he was the Mayor of Dixon.44

"General Joseph M. Street" — General Joseph Montfort Street (October 18, 1782 – May 5, 1840), was a frontiersman in the old Northwest Territory, and a friend of Henry Clay, Andrew Jackson, and Zachary Taylor. After a stormy career as a newspaper owner in Kentucky, he established himself in Shawneetown, Illinois, in 1812. He was made general of the local militia. In 1827 he became the Indian agent to the Hocągara. He attempted to keep white settlers out of the lands reserved for the tribe, but it proved a hopeless task, so he came to believe that Indian removal was the only answer. In 1832, he was able to keep most of the Hocągara neutral in the Black Hawk War. In 1834, the Fox and Sac were added as his charges. This diffusion of his labors caused the abortion of his school for the Hocągara at Prairie du Chien, which closed the year that he died.

|

| Governor Reynolds |

"John Reynolds" — John Reynolds was born on February 26, 1788 to Robert Reynolds and Margaret Moore, who had immigrated from Ireland to Philadelphia in 1785. In the year of his birth, the family moved to Tennessee country, but incidents with the Indians caused them to pull up stakes and move to the interior of the state. In 1800, they moved to Kaskaskia, Illinois. In 1808, he went back to Knoxville to study law and classics, but returned early due to his health. When the War of 1812 broke out, he served as a Private, then a Sergeant, in a Ranger unit operating in the west against the Indians, earning for himself the sobriquet, "the Old Ranger." In 1818, he was made an Associate Justice in the Illinois Supreme Court. He served in the Illinois House of Representatives, 1826-1830. In 1830, he was elected Governor of Illinois. Two years later, the Black Hawk War erupted, and he called out the Militia in response. He took the role of field commander of the force in the field, and was made Major General by President Jackson. In 1834, he resigned as Governor in order to accept a seat in the U. S. House of Representatives. This position he held until 1843. He served in the Illinois House of Representatives from 1846-1848 and as Speaker from 1852-1854. In 1860, he was a delegate to the Democratic National Convention, where he supported John C. Breckinridge for president. He died in Belleville, Illinois, in May 8, 1865.45

"Joseph Ogee" — Joe Ogee, himself half French and half Indian, had set up the ferry there in 1828, and later had a part in running its first post office. He established a "setting pole" ferry boat in the spring of 1828, the initial attempt by Bogardus to established a ferry the year before, met with the disapproval of the Hocągara, who expressed this by burning the boat.46 The next year, Ogee and his Potawatomi wife had a falling out, and she left him. Not long after, in 1830, John Dixon purchased both the ferry and surrounding region. The town that sprang up there in Lee County, Illinois, is named "Dixon" after him.47

|

| Sharon Howell |

| The Grave of Jules de Mun and His Wife |

"Julius DeMunn" — born Jules de Mun in Haiti, 1782. His aristocratic family, having returned to France, found it necessary to flee in 1790, setting up in St. Louis. He married Isabelle, the sister of Henry Gratiot. In 1815-1817, he, along with A. P. Chouteau, engaged in a long expedition through what is now Colorado to tap into this little exploited source of furs. However, word got out to the Spanish Governor, who sent troops to seize him and his supply of furs. When told by de Mun that he had the permission of the U. S. Government to be there, the Spanish Governor natural became enraged, since there was no doubt whatever that the territory lay well inside the Spanish dominions. De Mun was clapped in irons for 45 days, then court-martialed. The Governor insisted that he be shot, but his court martial instead had his furs seized and mounted him on poor horses to return to St. Louis. Much later, he set himself up as an Indian trader about 8 miles up Sugar Creek from White Breast's village (see the map above). When the Black Hawk War broke out in 1832, de Mun fled. His trading post was looted and burned to the ground, and its proprietor never returned. He lived out the remainder of his days as a petty clerk in St. Louis, and was never recompensed by the government for this $2,000 loss.48

"grease" — waséra actually means "paint."

"Pay-chunka, or Chief Crane" — this is for Pecąga, "Crane," where the word pecą appears to denote cranes, herons, and egrets collectively. In 1816 he was said to have lived in the area of Prophetstown. He is mentioned in an interesting story from this time.

(865) Shortly after [John Davenport] had commenced trading up Rock river he made a very narrow escape. About this time several war parties had gone to attack the settlements, one of which had been unfortunate and had lost some of their men, so that, on their return, the relations of those that were killed felt very hostile and determined to be revenged at the first opportunity. Not knowing anything of this state of things Mr. Davenport packed up some goods on four or five horses, taking Gokey with him, and started up Rock river. They arrived at Prophetstown and went immediately to their old friend, Wetaico's [Wit’ega ? Wait’ega ?] lodge. The old man met them but seemed much alarmed. He shook them by the hand and said he was very sorry they had come at this time; he was afraid they would be killed as there was a war party just about to start from the upper end of the village, headed by the "Crane," who had lost some relatives, but that he would do all he could to save them. This was said to them in the Chippewa tongue as that was generally used by the traders. He invited them to sit down, when the yells of an approaching party of Indians were heard. He told them to keep cool and show no signs of alarm. In a few minutes a large crowd surrounded the lodge, (866) whooping and yelling like so many devils. The old man now stepped to the door of his lodge and inquired what they wanted (in the Winnebago language.) They replied that "they had come to kill the white men." The old man now made them a long speech, claiming the rights of hospitality and the sacredness of his lodge. He told them they were fools! Why be in so great a hurry? That they had plenty of time, as the trader was going to encamp just below the village and would remain three or four days to trade! This seemed reasonable and the crowd assented to it and retired. The old man returned and said he could save them, but they must follow strictly his counsel.

[Davenport and his men make a dramatic escape at night.] Sometime afterwards "Old Wetaico" visited Rock Island, when he gave an account of what occurred. The next morning after the escape, he said, the whole village turned out — men, women, and children, marched down to the tent headed by the "Crane" and his war party, armed with their tomahawks, bows and arrows, and painted — singing their "war song," and beating their drums. They advanced, dancing their war dance, and surrounded the tent. But they soon found "that white man is very uncertain." Owing to the bad feeling of this part of the tribe, he did not go among them for some time afterward. The Winnebagoes frequently came down to the Island to trade, in small parties, but they appeared very sullen and shy. They did not like to visit the Fort much. Mr. Davenport felt satisfied that if they got a good opportunity they would kill some of the whites.49

In 1819, Crane showed up at Davenport's store late in the day with a party with him saying he wished to trade. They spend the night, at which time Crane hoped to attack them in their sleep, but an accidental noise woke everyone up, and the door between the whites and the Indians was barricaded. During the night, the warparty slipped out. The next day they ambushed and scalped two soldiers.50 After 1819, Crane next shows up as the signatory of the Treaty of 1829, along with Whirling Thunder.51 However, in connection with the Black Hawk War, Henry Gratiot wrote in 1831 that John Dougherty had informed him that

the Crane, one of the leading War Chiefs, visited him, and assured him that they had no wish to take a hand in the affair. That the whole Nation were occupied in the tilling of their ground.52

In 1833 he attended the Four Lakes Council.53 According to account books, he was a frequent customer of John Dixon.54

"Blue Coat" — this would be Wonąžįcoga in Hocąk. Apart from being mentioned in Dixon's account book,55 he remains an obscure figure.

|

| George Catlin |

| Mąnąpega |

"Old Soldier" — the word xųnų́ can be translated as either "little" or "young"; likewise, the word xete can be translated as either "big" or "old," so the name would likely have been Mąnąpe-xete-ga. However, his name might well have been simply Mąnąpega, "Soldier," the "Old" having been added on account of his age. Such a chief is known from this time period and was painted by George Catlin. He was called "Soldier," Mąnąpega, and does, in this painting from the early ’30s, appear to be an elder. The role of "soldier" was taken exclusively by the Bear Clan, and really expresses the vocation of police officer. Nevertheless, it still retains connotations of special warrior qualities, and so could be a nickname won by a member of the Thunderbird Clan, from which village chiefs were drawn. Another possibility is that he was a chief in the Bear Clan, although as such he would not likely have been the head of a village.

|

| Charles Bird King |

| The Shawnee Prophet |

"Shawnee Prophet" — the brother of Tecumseh, whose Shawnee name was Tenskwatawa. He preached a return to the purely Indian way of life, demonstrating a self-reliance that would free them from dependency on the white man and especially his whiskey. The Hocągara have detailed stories about him: see "What the Shawnee Prophet Told the Hocągara," and "The Shawnee Prophet and His Ascension."

Notes to the Commentary

1 Linda M. Waggoner, "Neither White Men Nor Indians": Affidavits from the Winnebago Mixed-blood Claim Commissions, Prairie Du Chien, Wisconsin, 1838-1839 (Roseville, MN: Park Genealogical Books, 2002) 22b. Norton William Jipson, Story of the Winnebagoes (Chicago: The Chicago Historical Society, 1923) 234-235. This is an unpublished typescript.

2 Dan L. Thrapp, Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography: In Three Volumes, Volume I (A-F) (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1988).

3 The Past and Present of Rock Island County, Ill. (Chicago: A. F. Kent & Co., 1877) 116, 118.

4 Mrs. Mary Ann Brevoot Bristol, "Reminiscences of the Northwest," Lyman C. Draper, Wisconsin Historical Collections, VIII (1879): 293-308 [8:301 note].

5 Josiah Seymour Currey, Chicago: Its History and Its Builders, 3 vols. (Chicago: S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1918) 1:129-130.

6 Juliette Augusta McGill Kinzie, Wau-Bun, The "Early Day" in the North-west (New York: Derby & Jackson; Cincinnati: H. W. Derby & Co., 1856) 84.

7 Waggoner, Neither White Men Nor Indians, 21-22.

8 John T. de la Ronde, "Personal Narrative," Wisconsin Historical Collections, VII (1876): 345-365 [350].

9 Charles Philip Hexom, Indian History of Winneshiek County (Decorah, Iowa: A. K. Bailey and Son, Inc., 1913) 32.

10 Daniel M. Parkinson, "Pioneer Life in Wisconsin, Wisconsin Historical Collections, II (1903 [1856]): 326-364 [338-340]; Charles Bracken, "Further Strictures on Ford's Black Hawk War," Wisconsin Historical Collections, II (1903 [1856]): 402-414 [404-410].

11 Charles E. Brown, "The White Crow Memorial Pilgrimage," Jefferson County Union (Oct. 20, 1918) 1-10 [8].

12 Brown, "The White Crow Memorial Pilgrimage," 3.

13 Col. Daniel M. Parkison, "Pioneer Life in Wisconsin," Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, I-II (1855): 326-[339].

14 Brown, "The White Crow Memorial Pilgrimage," 7. "Additions and Corrections," Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, X (1888): 496 (to II, 354).

15 "Indian Honor: An Incident of the Winnebago War," Wisconsin Historical Collections, Vol. V (1868): 154-155 = Western Courier, Ravenna, Ohio, February 26, 1830.

16 Lurie, "A Check List of Treaty Signers by Clan Affiliation," 58, name 31.

17 Charles Bent, History of Whiteside County, Illinois, from Its First Settlement to the Present Time (Morristown: L. P. Allen, 1877) 524.

18 Norton William Jipson, Story of the Winnebagoes (Chicago: The Chicago Historical Society, 1923) 231.

19 Theron Royal Woodward, Dodge Genealogy: Descendants of Tristram Dodge (Chicago: Lanward Publishing Co., 1904) 60.

20 Louis Pelzer, Henry Dodge (Iowa City: State Historical Society of Iowa, 1911). Reuben Gold Thwaites, Notes to Wau-Bun, Caxton Club Edition (1901), 416 nt. 112.

21 Willard Carl Klunder, Lewis Cass and the Politics of Moderation (Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1996). Andrew Cunningham McLaughlin, Lewis Cass (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1892).