Gottschall: A New Interpretation

by Richard L. Dieterle

Contents

The Interpretation

The Painting and Siouan Prehistory

The Battle of the Twins with the Thunderbirds

The Figures of the Twins

The Red Paint on the Image of Ghost

The Double Helix

The Rayed Orbs

The Nestlings

Great Black Hawk

Blankets Lost and Found

The Red Horn Figure and the Mother of the Twins

Bluehorn and the Pipe Smoker

The Seven Rays of the Orbs

The Seven Helices of Ghost's "Apron"

The Turtle Figure

Conclusions

Comparative Material

Debate and Discussion (now found in a separate file)

The Painting and Siouan Prehistory. The Gottschall rock shelter (not quite a cave) is located near Muscoda, Wisconsin, in Iowa County which is in the southwestern part of the state,1 an area that came to be within the Hocąk hunting grounds, sometime after the ill fortunes the French visited upon the Fox nation. However, prior to the Sauk and Fox invasion of ca. 1640, the area may well have been occupied by the Hocągara. The site contains about 40 pictographs. One of these, Panel 5, is of special interest, since it is a single composition that almost certainly deals with mythological themes. Panel 5 is also known as the "Red Horn" panel on the basis of its interpretation as an incident in that demigod's adventures on earth. It is this interpretation that I wish to reëxamine.

Panel 5 can be dated, it is said "confidently," to the Xᵀᴴ century A. D.2 This has certain immediate consequences when trying to associate it with any social group, especially one defined by language, since language and material culture have only a low degree of correlation. It is difficult to proceed on the issue of the antiquity of the Hocąk nation, since glottochronologies done on Siouan have come to absurdly divergent conclusions, bringing into question the methodology itself. Springer and Witkowski have calculated that Hocąk has existed as such since about 1500 A. D., when it and the kindred Chiwere peoples (Oto, Ioway, Missouria) separated from one another.3 However, Grimm has calculated the date of Common Winnebago-Chiwere at 1000 A. D., an incredible half millennium older!4 How much further back in time one can go before the language spoken by the predecessor people becomes unintelligible to modern Hocąk speakers is an open question. What is said of the language can also be said to an unknown degree of the mythology. The stories of the Chiwere people show considerable divergence (indeed even within that language group), suggesting that the stories of the Common Winnebago-Chiwere peoples may have been significantly different from the daughter stories existing today. The problem deepens as we recede into ever more remote regions of the past. The divergence of the Dhegiha Sioux speaking tribes (Omaha, Ponca, Osage, Quapah, and Kansa) from the Winnebago-Chiwere is dated at ca. 1000 A. D. by Springer and Witkowski, and 1 A. D. by Grimm. At that depth of time, it becomes very difficult to say anything about what stories may have existed.

However, some stories should remain stable over long periods of time, since they address an immutable subject matter. It is this fact that explains how myths from widely separated and completely isolated places can be almost identical. One of the stories about Bluehorn, for instance, is very close to a medieval Irish story about CuCulainn and CuRoi MacDairi (see the Comparative Material to Bluehorn's Nephews). The explanation for their convergence despite immense spatial separation can be used to account for similarities between stories separated by huge expanses of time. Allegorical stories that are about, say, stellar phenomena may be highly stable, since their subject matter is not very likely to change. Allegories about the same thing, given the constancy of the rules of interpretation that define allegories, would necessitate similarities in the stories. A story about a stable phenomenon could even arise more than once in history, as well as in more than one place, rather like the emergence of phytosaurs and crocodiles during the course of geological time.

We also may have to consider that the dating is wrong, despite high degrees of confidence in the date proffered. If this is the case, then scenes reminiscent of stories in the current repertory may date to a time in the not too distant pass, a time close enough to our own that these stories have passed down to us essentially unchanged.

We are able to show the whole of Panel 5 by the kind permission of the authors and Prairie Smoke Press, the publishers of The Gottschall Rockshelter, an Archaeological Mystery.5 The pictographs of this panel were meticulously traced by Mary Steinhauer.

The Battle of the Twins with the Thunderbirds. The characters portrayed in Panel 5 do indeed correspond to familiar characters in Hocąk stories, and the central actions of this panel fit rather nicely a particular story. This is the tale of the battle of the Twins with the Thunderbirds. This is but an episode in a whole panoply of adventures in which the Twins go someplace that their father has forbidden them to visit. There exist several versions of this story. A lesser known version is found in "The Lost Blanket," a story in which the Twins travel the world looking for a mink blanket that was stolen from one of them. In their travels to forbidden places they find something unusual —

One day they came to some incredibly steep cliffs, so they said to each other, "Let's climb these odd looking cliffs." When they finally reached the top, there, unexpectedly, were two bird's nests. In each was a nestling still covered with down feathers. "Look," they said to each other, "these nests have birds in them." They stood there gawking at the nestlings. They noticed that one had blue feathers under his wings. They said to each other, "Those will become beautiful feathers when these birds grow up — imagine what the adults must look like." Then they said to one of them, "So what do they call you?" He replied, "My parents have named me 'Breaks the Tree Tops'." They kept saying to each other, "Now 'Breaks the Tree Tops' is a strange name." Then they asked the other bird, "And what do they call you?" He replied, "My parents have named me 'Smashes the Tree Tops'." "The name 'Smashes the Tree Tops' is certainly an odd one," they said to each other. "Well, now, Breaks the Tree Tops," they said, "about when do your parents generally come home?" "Oh," he replied, "they will come whenever we call them." The boys said, "Well then, go ahead and call them." So Breaks the Tree Tops said, "All right." He called them by singing this song:

Come back and see us,

Come back and see us;

The Twins who are traveling as if crazy over this earth,

Have come upon us.

Come back and see us.Thunder could be heard on the horizon. The Twins said, "Smashes the Tree Tops, you call them too." So he called them by singing,

Come back and see us,

Come back and see us;

The Twins who are traveling as if crazy over this earth,

Have come upon us.

Come back and see us.When the birds spoke of them as "crazy," the younger brother got angry. Just then, with a loud thundering noise, the parents showed up. They were not alone. There were many that came flying, and now they were about to land. The boys said to one another, "There sure are a lot of pigeons here! Let's see if we can kill a few." The boys chucked stones at them and in this way they knocked a few down. The birds tried as hard as they could to kill the boys, but nothing they could do would hurt them. Werakirakuni! right in the middle of the fight, there unexpectedly was a bird wrapped with the boy's mink blanket. The boy knocked him down with a rock, and snatched the blanket off his body. The birds said, "We had better call it quits before they kill every one of us!" So they stopped attacking the Twins. These birds are the ones that they call "Thunders."6

In the "Lost Blanket," the Twins are said to have fought the Thunderbirds with stones, but only later do we discover that they killed the Thunderbird nestlings. In most versions, this is the story's focus. For the related Ioway tribe, the nestlings are pictured as little winged men, four in number, whom the Twins (Dore and Wahrétua) put in an otterskin bag. The Ioway Twins are attacked by lightning, but instead of fighting back, they merely find clever ways of avoiding being struck. When they take the Thunders home to their father, he is horrified and orders the boys to return them to their nests.7 In this unpublished version of the Hocąk tale, "The Twins Disobey Their Father," Jasper Blowsnake goes into some detail about the confrontation between the Twins and the Thunder nestlings.

(21) Then they used to be at the lodge. Now again he told them, "My sons, over there in a southern direction, (22) there is a hill whose cliffs are covered with red cedar, that hill is a hill of frightening aspect. Do not go over there," he said. He went hunting. As soon as he had gone, a little later the one who has a stump for a grandmother said, "Flesh, right away your father ordered us to go south to the hill. Right away we will go." Flesh said, "Koté, instead father forbade us." "Koté, again it is very good, so let's go right now. If you don't, I'll cut you with my beaver teeth," he said to him. "Okay, then I will go," said Flesh. They left. They reached that hill. They were all over that hill. Afterwards, they did not learn a thing. They went to the very top. There were four birds with bare stomachs there. "Korá Flesh, there are four things here." (23) He asked one of them, "By what name do they call you?" he said to him. The one who has a stump for a grandmother said it. That bare-bellied bird said, "They call me 'He who Strikes Trees'," he said. "Korá, you're a great one that they call 'He who Strikes Trees'. You that speak, even I am not called 'He who Strikes the Trees'," he said. He kicked him with his toes. Then again another one he asked, "You who are also smart, what do they call you?" "And what should they call me? They call me 'He who Breaks the Tree Tops'." Korá, you're a great thing that they supposedly call 'He who Breaks the Tree Tops'. Not even I myself am called 'He who Breaks the Tree Tops' and he kicked him with his toes. And again said to one of them, "You who are also smart, what do they call you?" he said to him. "What are you called?" "They call me 'Storms as He Walks'." When he had said this, "Kará, you're a great one whom they would call 'Storms as He Walks'. (24) Even up above I am not called 'Storms as He Walks' and he kicked him with his toes. He kicked him so that he rolled off. He spared the last one left. Again he said to him, "Also, what do they call you who are so smart?" he said to him. He said, "What did my older brothers tell you their names were as you were kicking them?" he said to him. "Koté žigé (come on now), it would be very good if you told it. If you don't tell it, I'll squash you," he told him. And that bird said, "What should they call me? When I was named they called me 'Rains as He Walks'." "Kará, what a great thing you must be that they would call you 'Rains as He Walks'. Up above, even I myself, they do not call 'Rains as He Walks'," he said and he kicked him with his toes. He kicked him so that he made him go rolling along. (25) And he said to them, "What do you say to cause your parents to come?" "When we call them, they always come back." "Then say it." Then they said it. They called their parents. They said,

We see, we see;

The Twins go about the world crazed;

They have come upon us, they have come upon us!After that, he kicked them. They got angry. "Because you are crazed upon the earth, you are in the wilderness atop a hill." At the horizon they made roaring sounds. "Koté žigé (come on), say it." "When we say it, you start kicking us." "Koté, if you don't say it, I will squash you with my feet." Again they said it. They summoned their parents:

We see, we see;

The Twins go about the world crazed;

They have come upon us, they have come upon us!The clouds fell dark. "Say it again." "When we say it, you kick us." "Now say it! (26) If you don't say it, I'll squash you." They were afraid of him. They said,

We see, we see;

The Twins go about the world crazed;

They have come upon us, they have come upon us!"Because you are crazed upon the earth, you are in the wilderness atop a hill." After they said it — korá! — a great many of them were coming. Immediately, again for the fourth time, he had them say it. They objected, but

We see, we see;

The Twins go about the world crazed;

They have come upon us, they have come upon us!"Because you are crazed upon the earth, you are in the wilderness atop a hill," he said. He kicked him with his toes. Right away as they had returned, they were already, even now, struck at. They squashed those bare bellied birds. Right away a great many came. "Flesh, your father used to call them 'pigeons'. That's what kind they are. Let's knock down pigeons." They did a lot of pigeon bashing. Flesh was the very first one killed. "Flesh, knocking down pigeons is such a pleasure, yet you're sleeping," he said. He got up. (27) Once he did, he did a lot of pigeon bashing. In trying to kill them they also did very much, but they were killing pigeons. Then when they knocked down one of the pigeons, they would clap their mouths and give a mighty shout for themselves. These pigeons would continuously come down lower and lower. These twins would go down lower and lower too. They were killing many of them. They were knocking them down. Then they killed the one who had a stump for a grandmother. The pigeons did it. Flesh said, "Koté, get up, while knocking down pigeons is proving so pleasant, you're sleeping, get up. "Ho," he said. Having gotten up to some extent, he started in again to fight the pigeons. They killed Flesh again. "In truth, kode, while the pleasure of knocking down pigeons is going on, you're sleeping," he said. He got up. "Ho," he said. Right away they started knocking them down. (28) They frequently knocked down pigeons. Having struck one of them down, they would give a shout. As a matter of fact, they killed the one who has a stump for a grandmother. Flesh said, "Koté, while such pleasantries are going on, you're sleeping," he said to him, and he got up. Their father, while he was hunting in the area, the Thunders started coming back. Mightily they started to return. He knew of it. He knew immediately that his sons were rushing back. "Hoxhó my sons, at last you will be killed." These Thunderbirds gave up, because they knew they were not going to kill them (the Twins).8

There are many other Twin tales of the fight with the Thunderbirds.9 The scene in Panel 5 seems to fit the incident that we might describe as "The Battle between the Twins and the Thunderbirds." Under this interpretation, the two human figures to the far left are the Twins, the two small birds, one of which is upside down, are the Thunder nestlings, and the large bird is, as has been suggested by Bob Salzer et alia, a full grown Thunderbird.10 The figure behind this Thunderbird, ought to be their father, but I think that this is probably an auxiliary figure pertinent to myth of the Twins, but not integral to the action. The same is true of the pipe smoker, who is at sufficient remove from the other figures that it is less tempting to include him in the action. The turtle figure above is a problem for this interpretation, but not an insurmountable one. More will be said on these alleged auxiliary figures as the interpretation progresses.

The Figures of the Twins. The two Hocąk Twins are known as "Flesh" and "(Little) Ghost." The latter is sometimes not referred to by name at all, but by an elliptic description (for reasons of taboo?), as "the one who has a stump for a grandmother." Radin simply adopted the name "Stump" as shorthand. The received interpretation sees these two figures as Giants and the mythic incident as the lacrosse game between Redhorn and his allies and the Giants and their confederates, with the pipe smoker being outside the scene.11 Giants are said to be four times larger than ordinary men, but this is not reflected in the painting. However, it is possible to put too much emphasis upon scale, inasmuch as perspective is not a salient feature in pictographic art any more than it was in, say, medieval Western art. Size may have something to do with power as much as physical dimensions (a paradigm in ancient Egyptian art, for instance). Just the same, why are the two figures on the left not identical, if they are meant to depict the Twins? The answer is simple enough. While the Twins were very similar, they were not actually identical. The youngest Twin, Ghost, was smaller, yet he was significantly stronger than his brother. He was also more audacious, and it was he who started the confrontation with the Thunderbirds. Therefore, the smaller leading figure should be Ghost. By exclusion, then, the trailing figure is Flesh. Ghost had another singular feature: beaver teeth with which he occasionally threatened to bite his brother. This may explain the painted design on Ghost's mouth area. Just below his nose and extending down his chin is a solid coloring which seems to indicate facial paint. The Hocągara have a name for this area of the face, pųc´, being defined in one sense as, "the area of the upper and lower jaw from under the nose down to the chin."13 This paint pattern has a fair resemblance to the light patch under the nose and extending to the chin of beavers, as we see in this Audubon painting below:

This pattern of coloration on the pųc shows somewhat better on the beaver to the left. The Hocąk call the chin portion of the pųc the "hair-jaw," hi-rap. The same word, rap, that denotes the jaw also denotes beavers. So the jaw is the "beaver," perhaps for the same reason that female pubes are so called in colloquial English. The beaver also has a line that separates dark hair above from lighter hair below. This line extends from the bridge of his nose to his ear, rather like the paint or tattoo lines seen on the Twins in Panel 5. The pipe smoker of Panel 4 has such a line as well, only it divides an upper light colored area from a lower dark space. It is not clear why Flesh would exhibit this line, so it may not have anything to do with beavers, although it is an interesting correlation in this context. The beaver affinities express Ghost's relationship with wood. His grandmother is a stump, and in one version he was buried or abandoned at the foot of a tree. [For the identity of one of the Twins with beavers, see Comparative Material below.]

The two Twins are said to have only single eagle feathers as headdresses, and Ghost does have what appears to be an upright feather as part of his head gear, but he also has a ribbon-like pair of trailing streamers as well, which is beyond what is said of them in the Hocąk literature. The Flesh figure seems to have numerous wide ribbon-like streamers as his headdress, but it is harder to make out a single eagle feather, although one might be present. Given the age assigned to this painting, it is not a significant divergence; indeed, we do not know how essential the lone eagle feather was among Hocąk variants, since it is only mentioned in one of them. Originally, they were said to have turkey bladders or mammal placentas as headdresses. There is no hint of such head gear in the pictograph. Flesh is dressed in leggings, whereas Ghost seems to have more elaborate apparel consisting of an oval disc over his chest (which we can probably call a "gorget") and something which might be described as an "apron" just below it. His figure is cut off too high to know what he is wearing below his waist. In addition, both he and his brother are wearing some kind of long hair or fringe ornament on their left arms only, apparently the same item as is worn on the figure at the extreme right of the composition, only in that person's case, the ornament (and bowstring guard) is worn only on the right wrist. Some of these accouterments can be seen in Hocąk garb as late as the XIXᵀᴴ century. In a painting of a Hocąk warrior of the Elk Clan by the name of Little Elk (Hųwąnįka), we see many similarities to Ghost's costume. This rendering of Little Elk was made by George Catlin in the 1830's:

The gorget suspended over Hųwąnįka's abdomen by what appears to be a leather strap, has a good resemblance to the rather schematic oval worn slightly higher on the "Ghost" figure. Only a little below Ghost's disc is some kind of rectangular "apron" with vertical, double helix designs and fringe on its lower border. This matches nicely the apron worn by Hųwąnįka, although the latter is not shown to have any decoration on its surface. It can be seen from the painting that it, like its counterpart from Panel 5, is worn above the level of the breach cloth. He too is wearing a headdress with a single eagle feather, although it is not oriented upright as it is with Ghost. Some of the depicted costume elements are seen even more pronouncedly in this Catlin painting of The Crow (tribe not identified) seen below at the left:

|

|

He too has the gorget and the "apron," and furthermore, he has a wrist band with a fur suspended from it, a style very similar to that of most of the figures in Panel 5, who may have rawhide strips or strands of hair instead of fur. He too wears this on his left arm only. Like Flesh, he has a band on his upper arm, although in the Catlin painting, The Crow has two such bands. However, he also has a number of ornaments (strips of some kind) hanging from his upper left armband only, a feature also found in the depiction of Flesh. The subject of the Catlin painting is wearing his gorget bare chested, just like Ghost in the pictograph. This painting of recent vintage shows that such a style of dress is purely masculine, as pictures of women show them clothed from head to ankle in dresses. So it is highly unlikely that this is a depiction, as has been suggested, of Redhorn's female lacrosse opponent (known in one source as "Pretty Woman"), even if we allow the unattested supposition that she dressed like a man, since an oval gorget like the one depicted on Ghost would rest pretty uncomfortably on a woman. Another Catlin painting of Four Bears, a Mandan warrior from the 1830's (shown above right), depicts him wearing an oval form of the gorget, demonstrating that an oblong variant was extant this recently.

The Red Paint on the Image of Ghost. There are two sets of things painted red on the image of Ghost. One area, which we have explored, is around his mouth; the other is a pair of streamers or ribbonlike structures that form part of a headdress of some kind. The streamers seem to be of light material since one of them at least curls over on itself as if blowing in the wind. The obvious candidate would be horse's hair, but that is ruled out, since we are told that the painting dates from the Xᵀᴴ century A. D. It could be dyed human hair. However, the suggestion of the archaeologists that this is a woman and that "her" hair is red is a gross misperception precipitated by forcing a thesis. Not only is the figure a young man, but it must be pointed out that the hair on top of his head is not painted red, so clearly he can't be called "red headed." The streamers are bound up with the upright feather that constitutes his otherwise rather minimal headdress. Knotted headdresses with an upright eagle feather and a trailing streamer are found in Mississippian culture, at the Spiro Mound in Oklahoma they are seen in Braden B and C phases.12 Some of these are shown below in comparison to the headdress of Ghost at Gottschall.

The tonsures of the Mississippian images are similar but not identical to those of Gottschall. The first example shows a knotted headdress with an upright feather attached to it and a streamer following behind.14 This may be what we are seeing at Gottschall. Instead of a solar-like disc with a double helix emanating from it, the Mississippian image shows a double helix looped around the eye. A simpler version is presented in the second example, where the knot is not in evidence (due to the simplicity of the drawing).15 Its streamer may be of human hair. As in the case of Ghost, the feather and the streamer are affixed to the hair. The third example shows the typically more elaborate version of this headdress characteristic of Mississippian culture.16 However Ghost's headdress was made, what seems important is that the artist went out of his way to paint it red. What does the literature on Ghost say about a red headdress? To answer this we must understand the meaning of the headdress in the Twins Cycle.

In a transparent allegory, Ghost sojourns awhile with Flesh then suddenly departs carrying away his twin's arrows (mą, also meaning "winter, years, time"). He also causes Flesh to forget everything about the period of their togetherness. When Flesh's father (the Sun) helps Flesh reunite with his twin Ghost on a longer term basis, he has to find a way to prevent Ghost from escaping into his preferred medium of water. This is done through a headdress. The device could have been affixed almost anywhere, but the head was chosen as the preferred site. It is the head that carries the greatest magnetism for the soul. It is said that when a fallen warrior's head is taken by his enemies, the ghost follows after it causing the man carrying its head to stumble (symbolic death and therefore symbolic revenge), a terrifying experience when understood as a confrontation with a hostile supernatural force. Nevertheless, whoever takes the head has some command over the soul associated with it and can at least direct the ghost to serve as a guide to his departed kinsmen when they must walk the road to Spiritland. Why is the head such a repository for the soul? In ancient Greece, and throughout the world among traditional cultures, the psyche has a special attachment to the head because it is there that the essential fluid of life, the muelos (μυελός), that constitutes marrow in the bones, is found in its greatest concentration.17 The brain is thought to be a massive assemblage of muelos and therefore the seat of the psyche. The Hocągara have a similar conception of the brain. Their word for marrow is wa-horugóp, which is a descriptive term meaning, "that which is scooped out."18 This is in reference to the marrow of animal bones, which must be scraped out to be eaten. The brain is called, nąsu horugóp > nąsurugóp, which is to say, "the (wa-)horugóp of the head."19 The soul's seat is the innermost part of a person's being, which in this case is literally the innermost reaches of a person's bones. Even people eaten by Giants can be brought back to life by taking the bones of the Giants who had eaten them and grinding them up into a powder, then yelling something that would frighten a human being, such as, "Run, the enemy is upon us!" (cf. The Sons of Redhorn Find Their Father, Partridge's Older Brother, Grandfather's Two Families, The Woman who Loved Her Half-Brother) The same procedure used by a powerful spirit over the bones of the deceased when completely reassembled, will have the same results (The Raccoon Coat, Redhorn's Sons, White Wolf). This formula is based upon the relation of the word nąǧi(re) meaning "to be frightened, fear" to nąǧi, "soul." By instilling fear, one instills the soul back into the bones. Once this happens, they come back to life. In the reverse process, when the nąǧirak meets Spirit Woman on the path to Spiritland, after feeding the ghost, she cracks open his skull, which is his final death. So it is little wonder that where the wahorugóp is most concentrated is the place most associated with the soul. This is why it is a head-dress that is most effective in governing the actions of the soul. In the more modern stories this headdress is made of an inflated turkey bladder. The turkey is the bird of the arrow (mą), and therefore the bird of time (mą). This is because the turkey's feathers make up the vane of the arrow, its "wings," and give it the power of flight and accuracy. Rušewe, the Chief of Birds, the turkey that chases after the Twins, is the bird of the arrow of time. It is time that dogs the steps of Ghost and Flesh, and as we mortals all know, leads to their final separation. In this context, though, the turkey headdress keeps Ghost and Flesh together, since it was inflated with the breath of their father. The Hocąk verb meaning "to breathe," ni, also means, "to live." By a fortunate homonym, ni also means "water," the special abode of the soul. However, it is the ni inside the bladder that keeps the Ghost from escaping his companionship with Flesh, as every time Ghost tries to escape into the water, it bobs him right back up. The bladder is an organ of the bird of time that expels and repels water, the medium of the wild and free ghost, and insures that it must reside in the lodge of this earth with Flesh. It commands the lifetime which is the union of ghost and flesh. [For another discussion of the same subject, see The Gottschall Head.]

Now, just like the artist at Gottschall, the father of the Twins (Sun) goes out of his way to paint this life-giving bladder of breath-and-life the color red. Why do Ghost's headdresses in story and mural get painted red? The turkey bladder, which is usually filled with one kind of ni, water, that the ghost likes to inhabit, is now filled with another kind of ni, breath, which the ghost is made to inhabit when it is joined with the flesh. Now Ghost must inhabit the ni of the body: the breath (ni), muelos (wa-horugóp), and perhaps the blood (wa'į). The headdress is what forces Ghost to create life in the flesh, so it is painted the color of blood, the color of life. As we have seen, the color black symbolizes death. It is the color of the shadow, the manifestation of the nąǧirak outside the body; it is the color of darkness, the counterpart of unconsciousness. So black is also the color of mourning. The Nightspirits are the cause of darkness, and it is to them ultimately that the present Black Bear Subclan traces its origins. The Nightspirits who bring the darkness are the eastern opposites of the Thunders of the west, whose color, emblematic of lightning, is red. In The Roaster, when the humans contest the Giants in a mortal struggle, the Giants paint themselves black, the color of death, whereas the humans paint themselves the color of life, red. In Chief and Red Man when the red of the sky symbolic of the hero is extinguished, so too is his life. In the former case his death is made known in the sky when it loses all traces of red clouds and turns completely black. The association of life and vitality with the color red is seen in traditional dress, where only young people were allowed to wear red, the color co (blue/green) being the color of the elders. When a member of the Medicine Rite treads the Road of Life and Death into Spiritland, there are many things along the way whose color reminds him of the promise of eternal life. The second hill that he comes to is entirely red; at another place he sees a field of red rocks; in yet another spot he encounters red willows and reeds; and finally, he gazes back to see a valley covered by a red haze. However, the matter is complicated. The color red seems to be associated with the ghost (wanąǧi) itself. This is why the guardian of the gate to Spiritland in the west is Red Bear. The red bladder of ni that keeps Ghost from parting from his brother Flesh, recalls quite obviously that other red ni that is intimately bound with the seat of the mind (na'į), and that is blood (wa'į). The seat of the mind is the heart (nącge). It is here where most of the blood is concentrated, and which is in close proximity to the blood-rich lungs which cause the ebb and flow of the breath (ni). In the heart reside all the emotions and all the desires and wants of a person. When the Green Man (Bluehorn) replaced the heart of a deer with one fashioned of dried earth, it was said that ever after deer were skitterish because they had no moisture in their hearts. So the force of willful emotion is tied to the blood.20 In another account of the sojourn of the soul to Spiritland, the wanąǧi comes to Spirit Woman who then applies to him the latest medical technique of the XVIIIth century — she cups him. In this procedure, a heated cup is placed over the spot where the patient is to be bled. The function of the heated cup is to draw the blood up to the surface. There the sanguinous humour is bled off. So Spirit Woman takes the spiritual body of the ghost and removes its spiritual blood, which we are told leaves the wanąǧi free of all earthly wants and cares.21 It may now progress to Spiritland without anything holding it back. This shows us that it is the blood that makes the heart the seat of the mind. So to show that Ghost is sojourning with Flesh and that he is not in the bloodless condition of the departed soul, his head is graced with the color of blood and of life. The head, the seat of the life soul, is given the color of blood, the seat of the mind and of consciousness, to remind us that he is bonded to his twin brother Flesh, expressed in the fact that it is he who always takes the initiative and backs it with that force of emotion that exposure to blood must necessarily give him.

Now we must consider why the area around the mouth, the pųc, has been painted red in the depiction of Ghost. In the Hocąk language, the mouth has a special connection to the life force. The word for mouth is i, which is nearly identical with its nasalized version, į, 'į, meaning "to be, to become; to live, be alive."22 Since nothing in the world of religious thought is considered a matter of coincidence, but everything is pregnant with meaning, the seeming coincidences of homonyms and assonances are an expression of hidden meaning and were put into existence by the machinations of spiritual forces. So the mouth is in word intimately tied to life, to existence. Whether such ties existed in the Xᵀᴴ century is not critical to the thesis, since the mouth is the α and ω of breath, where it exits and enters. This breath is the carrier of life, and it ceases to ebb and flow only at death. It resides in the lungs and heart where the blood is most concentrated. Thus the ghost or soul is strongly associated with the blood and breath, and therefore also with the heart, lungs and mouth. So the region about the mouth of the dead is often painted the color of blood and life, red. In the Hawk Clan, or Warrior Clan as it was also known, sometimes the mouth was surrounded with a red circle. In pictographs the empty circle itself, as we shall show below and in detail in the Gottschall Head, denotes life. In time of war the paint was dispensed with and in its place the real article for which the red paint stood was used in its place — the circle was painted with human blood.23 In the Deer Clan Origin Myth it is said,

And he took red paint and said, "My brother, I am going to paint you. They will recognize you at home, for this is the way we are. Hereafter, all those men who are to live after, they also will all be doing like this. The story (worak) will be that he did the painting in just this way," he said. And he blackened his forehead with charcoal, and they streaked the corners of his eyes with red, and the chin and front of the throat he made red. And they dug a grave. There they buried him.24

The Bear Clan also paints the entire chin of the deceased red, the relevance of which to the Ghost figure at Gottschall was appreciated to some degree by Salzer.25 As we have seen in the discussion of the Gottschall head, the chin is a special area that expresses the life force in the form of beard growth. As we saw above, the chin is called hi-rap, "the hair jaw," the word for jaw (rap) also denoting beavers, so that the whole jaw becomes "the beaver" by homonym. The picture of Ghost at Gottschall has the red paint, symbolic of the life principle and therefore the soul, painted in the pattern of the beaver's coloration around its pųc or snout in order to show the water-loving affinities of the ghost, an affinity indulged in the flesh by its special associations with blood and wa-horugóp (marrow).

The Double Helix. All three of the humans on the same plane have something that has been described as a "forelock." This is another odd idea inspired by the slightly later Mississippian culture, where forelocks are quite pronounced, but by no means this pronounced. In the illustrations below, the rayed discs and the twisting lines emanating from them at the point of attachment have been aligned in the same direction for Ghost, Flesh, and their presumed mother.

In the depiction of Ghost, the first two lobes of the entwined lines look as if they were forelocks, but they are not drawn in exactly the same way as the rest of the strand, which reaches all the way to the ground and attaches to an inverted bird. Some forelock! The entwined lines either attach to the first two lobes or pass behind them, originating in either the disc or what looks very much like a Mississippian wooden cone.26 On the other two figures there is no ambiguity. The entwined lines originate in the rayed disc. In the case of Flesh, one of the rays is even below the attachment point. When this is appreciated, we realize that the entwined lines have something to do with the rayed discs or orbs.

In some ways the entwined lines resemble a length of chain, except that the links seem to be slightly oval in the vertical direction. When seen this way, it inscribes a two-dimensional view of a double helix, a crossing double spiral. This pattern, especially when connected to a superior disc, is highly significant. One place where we see the vertical ascending double (parallel) helix is in the plains Indian sign language. The sign for the concept conventionally translated into English as "medicine" is shown in the inset. This is not the sense of "medicine" applying to physical remedies, but the sense that expresses sacred power.27  In sign language this concept is expressed by forming a "V" with the index and middle fingers, then moving the hand upwards in a circular, clockwise motion.28 It may be observed that the tips of the fingers inscribe a double spiral. The advantage of the sign is that it expresses the concept in three dimensions with the inclusion of motion. The sign at once expresses duality, circularity, and vertical motion. In Hocąk thought, for instance, creation is from above. The earth itself was cast down by Earthmaker (Mą’ųna) from above, and its seas were his tears of loneliness that fell from on high. Offerings to the spirits in the other direction are made by sending the articles through the smoke hole of the lodge in which the rite takes place. Some offerings (such as tobacco) are placed in the fire, which is the "messenger of the spirits" since its smoke rises to the upper regions carrying the offerings to the spirits. So there is a double pathway of creation and effect, both upward and downward. This is the duality of the motion, the two strands of the basic rope, the double helix of an axis mundi that ties the mortal and immortal worlds together in a binding medium through which power is communicated. But this communication is also a circle in other ways. The circle is a perfect figure with neither beginning nor ending. When Hare attempted to win immortality for human beings, he did so by walking in a circle around the world or around a central fire; but when he looked back, he broke the perfect circularity of his Vision for humanity, and in so doing, shattered human immortality in the flesh. The double helix expresses the circle in motion. When Earthmaker created our world, he not only sent it downward, but his act of holy creation imparted a circular spin to it, so that it was in constant flux, the flux of infinite circular creativity. To render the earth quiet and stable, Earthmaker had to anchor it in place. In the Medicine Rite description of the journey to Spiritland, the departed ghost ascends to the world of his deliverance, the realm of Earthmaker himself, by climbing up a ladder whose right side is "like a twisted frog's leg." This staircase to heaven is a static representation of the double helix of transformation, with the progress of soul ascending in conformity with this pattern, being transmitted to the realm of Spiritland to be transformed (see the Commentary to "The Journey to Spiritland"). This has an interesting exemplar in the Micmac petroglyph shown just below to the left. The caption reads, "Stars and lines said to represent the Milky Way, the 'Spirit Road' of the Micmac Indians. Micmac Incised style; ... Kejimkujik Lake, Nova Scotia."29

In sign language this concept is expressed by forming a "V" with the index and middle fingers, then moving the hand upwards in a circular, clockwise motion.28 It may be observed that the tips of the fingers inscribe a double spiral. The advantage of the sign is that it expresses the concept in three dimensions with the inclusion of motion. The sign at once expresses duality, circularity, and vertical motion. In Hocąk thought, for instance, creation is from above. The earth itself was cast down by Earthmaker (Mą’ųna) from above, and its seas were his tears of loneliness that fell from on high. Offerings to the spirits in the other direction are made by sending the articles through the smoke hole of the lodge in which the rite takes place. Some offerings (such as tobacco) are placed in the fire, which is the "messenger of the spirits" since its smoke rises to the upper regions carrying the offerings to the spirits. So there is a double pathway of creation and effect, both upward and downward. This is the duality of the motion, the two strands of the basic rope, the double helix of an axis mundi that ties the mortal and immortal worlds together in a binding medium through which power is communicated. But this communication is also a circle in other ways. The circle is a perfect figure with neither beginning nor ending. When Hare attempted to win immortality for human beings, he did so by walking in a circle around the world or around a central fire; but when he looked back, he broke the perfect circularity of his Vision for humanity, and in so doing, shattered human immortality in the flesh. The double helix expresses the circle in motion. When Earthmaker created our world, he not only sent it downward, but his act of holy creation imparted a circular spin to it, so that it was in constant flux, the flux of infinite circular creativity. To render the earth quiet and stable, Earthmaker had to anchor it in place. In the Medicine Rite description of the journey to Spiritland, the departed ghost ascends to the world of his deliverance, the realm of Earthmaker himself, by climbing up a ladder whose right side is "like a twisted frog's leg." This staircase to heaven is a static representation of the double helix of transformation, with the progress of soul ascending in conformity with this pattern, being transmitted to the realm of Spiritland to be transformed (see the Commentary to "The Journey to Spiritland"). This has an interesting exemplar in the Micmac petroglyph shown just below to the left. The caption reads, "Stars and lines said to represent the Milky Way, the 'Spirit Road' of the Micmac Indians. Micmac Incised style; ... Kejimkujik Lake, Nova Scotia."29

This is not a realistic representation of the Milky Way, but a symbolic rendering of a road of supernatural power, a connection between worlds like the twisted frog's leg of the Hocąk Medicine Rite, the rotating, double helix pathway to the Otherworld. Note that the star embedded in the Milky Way has a single helix "power line" descending downward, just like Gottschall has the double helix descending downward from each of the solar-like discs. Two more examples of the "double helix" design are found from the Great Lakes region. The one above right is described as an "unidentified abstract symbol," and the more diamond shaped one on the right is from the Cliff Lake paintings.30 Other examples are found in the Southwest and in Missouri.31 This "diamond chain" motif, as it is called, may not belong here, but is close enough in form to be worth mentioning. These last two have much the same orientation as those at Gottschall. Similar examples come from the living tradition of the contemporary Lakota, whose linguistic branch is thought to have separated from the Hocąk, Chiwere, and Dhegiha around 700 AD. The Lakota still use a minimal representation of this same double helix pattern (see insets). The fundamental unit of the structure is often represented as a triangle. However, the Keeper of the Star Map among the Oglalas reminds us that

the Lakota image of a star is not a flat two dimensional triangle, but rather a cone, a vortex of light slanted down. The inner true shape of the stars and the sun is an inverted tipi. Later that same week, a friend, Chris Horvath, told me [Ronald Goodman] he'd been taught by Leslie Fool Bull, a leader in the Native American Church, that the tipi is part of an image of sacred above and sacred below. They are reflections of each other. He made this drawing

x

Sacred above grandfather and sacred below grandmother represent the two cosmic principles which together form a unity, restoring a oneness to the One, and always and the only One — Wakañ Tañka. The Oglala star map ... is both a star map and an earth map. The complete symbol which embodies this complex knowledge is two vortices joined at their apexes.32

The two vortices joined at the apex form a symbol called kapemni. This term does more to express the truly dynamic and kinetic nature of the double vortices than its two dimensional counterpart might suggest. The stem is pemni, which means "twisting." The prefix ka- is used "for a class of verbs whose action is performed by ... the wind." The word in origin must have denoted the actions of tornadoes and dust devils, but is now used to express their general twisting motion. In the Oglala story of Iron Hawk, it is a whirlwind that sucks the hero Red Calf up through the hole in the sky where his father Iron Hawk is being held prisoner.33 This motion, expressed by two "V" shapes in mirror image of one another, recalls the Lakota "medicine" sign (see above). So the kapemni symbol

... is referring to two vortexes (two tipi shapes) joined at their apexes, and turning. ... Mr. Norbert Running, Medicine Man and Sun Dance leader on the Rosebud Reservation, explained that the Sun Dancers create with sacrifices and prayers an invisible tipi (or vortex) of praise as they dance around the holy tree at the center. Sun above, Sun Dancer below, and the connection between them is prayer."45

So the kapemni is a whirling set of vortices through which the upper and lower worlds communicate with one another. An act of supernatural power, such as a sacrifice or prayer can actually generate a kapemni. The double helices that we see in the Micmac petroglyph and at Gottschall are nothing more nor less that a series of connected kapemni. The kapemni certainly appears to have evolved out of what is called a "power line." This term is found in the literature on plains pictography, of which there are numerous Lakota examples.  Sometimes, though less frequently, it is represented by several straight lines emanating from the head of a supernaturally powerful person, such as a medicine man. More usually, however, the rays take on the form of sine waves, as we see in the Lakota pictographic symbol meaning "medicine man" [inset].46 The term "rays" is appropriate, since such depictions attempt to capture an invisible power, a supernatural force, that radiates outwards from a sacred nodal point. It is a person's or object's holiness expressed as an invisible field of supernatural potency. The sine wave is the two-dimensional representation of a twisting motion, since it is of the nature of radiating supernatural power to configure itself in this circular form, the circle being an exemplar of perfection. We see such a "power line" emanating from a star in the Micmac pictograph above. More importantly, we have relatively modern pictorial evidence of both the power line and the kapemni double helix that are reified in the form of concrete ritual artifacts.

Sometimes, though less frequently, it is represented by several straight lines emanating from the head of a supernaturally powerful person, such as a medicine man. More usually, however, the rays take on the form of sine waves, as we see in the Lakota pictographic symbol meaning "medicine man" [inset].46 The term "rays" is appropriate, since such depictions attempt to capture an invisible power, a supernatural force, that radiates outwards from a sacred nodal point. It is a person's or object's holiness expressed as an invisible field of supernatural potency. The sine wave is the two-dimensional representation of a twisting motion, since it is of the nature of radiating supernatural power to configure itself in this circular form, the circle being an exemplar of perfection. We see such a "power line" emanating from a star in the Micmac pictograph above. More importantly, we have relatively modern pictorial evidence of both the power line and the kapemni double helix that are reified in the form of concrete ritual artifacts.

A rather late survivor of the Mississippian culture, the Timucua tribe of Florida, was visited in 1564 by a French expedition under Laudonnière that had the foresight to bring an artist with them, Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues. He painted numerous scenes of Timucuan life which found themselves published in engravings done by the Flemish artist Theodor De Bry in 1591. De Bry's engraving of Le Moyne's "Trophies and Ceremonies after a Victory" is seen below.47

They elevated their "trophies" on seven poles. Of particular interest are rigid strands (vines?) that spiral down the poles, connecting the top of the trophy to the ground. The trophies are meant to be the surviving physical attachments to which the souls of the slain warriors remain fixed. The arm, scalp, and leg probably represent respectively, executive power, spirit, and motion. All the poles save one have single helices (spirals) or power lines that send down the spiritual power of the slain enemy warriors inherent in their appendages to the sacred earth of the victorious tribe. The scalps, which are a kind of synecdoche for the head as a whole, may be taken to represent the spirits of the departed warriors, whose powers now redound to the victors. The top knot, as can be seen, has been untied, and the long strands of hair have been allowed to spread out like wings. The result is similar to a κᾱρύκειον | caduceus (see below for the caduceus). The six poles on the right have a chiastic order: [a] hand, [b] scalp, [c] leg, [c] leg, [b] scalp, [a] hand. The last pole to the left is surmounted by a scalp, and represents an asymmetry. The poles are arranged in a semicircle, one complemented by the semicircle opposite them made up of the seated people, so that the whole forms a circle, with the quick and the dead opposite one another. The shadows show that the poles are arranged in an east-west axis. It is likely that the left extreme pole surmounted by a scalp is at the western extreme of the sequence, since that is where the spirit represented by the scalp goes at death (following the setting or "dying" sun). In the center of this circle of life and death is the priest opposite whom is found the drum, said by the Hocągara at least, to be the Messenger. The priest, a messenger himself, is communicating with the world of the Spirits, and is therefore appropriately placed in a Centre in Eliade's sense of the term.48 The poles also exemplify this notion of Centre. The number seven can be arrived at by taking the four compass directions on the ground, and adding the directions of up and down. The seventh "direction" is the center itself. The central pole of the seven is flanked by three poles on either side. It alone has the form of a double helix kapemni. It represents the Centre of special vertical communication that unites the spiritual Above World with the Below World of human affairs. As the staff of the Messenger, the caduceus has this same form. It is surmounted by wings, the power of locomotion for those beings who travel in the up/down axis, the same axis along which the communication of sacrifices and blessings are exchanged between humans and the Olympians. Among the Timucua, the pole is surmounted by the leg of one of the dead who is now walking to Spiritland. His locomotion is homologous to that of birds, and his ghostly leg is now like the wings of a bird, propelling him to the Above World of the spirits. The “other” seventh pole, the one on the extreme left representing presumably the west and therefore also this upper Spiritland, is surmounted by a scalp, the embodiment of the dead man’s own spirit. It is this spirit that leads the way and is the peripheral counterpart of the leg of the Centre. Like a caduceus, this pole of the Centre has a double helix, reflecting its special status as a conduit of power that operates in both directions, the upward direction of sacrifices and offerings, and the downward direction of blessings. This double helix looks very similar indeed to that portrayed in the Gottschall pictographs. The hoped for discharge of power is also in the same direction, from above to below. In the case of the Gottschall Twins pictures, the discharge of the force isn't a deposit of supernatural power into the earth, but a violent expression of its power to destructive ends. This kind of kapemni power is hinted at in rituals from the Mississippian cultures in the context of war: "... they strike with fury and vengeance the spiral-striped war pole — a symbolic axial conduit between the Sun and the sacred fire."49 There the spiral strips are a surface counterpart to the strands seen in the 1564 painting. The painting illustrates the ideal representation, which is three-dimensional. This three-dimensionality can only be suggested in the two-dimensional medium used at Gottschall. Nevertheless, among the Timucua we have a clear example of the spiritual power of the Above World of the sun expressing itself through the rotating vortex of the kapemni, which appears to be what is happening in an equally warlike context with the Children of the Sun at Gottschall.

Additional examples of the vertical, double helices come from older phases of the Mississippian culture, specifically from the Spiro Mound in Oklahoma (see the illustrations below). The first example is a fragment of a gorget showing the double helix arising directly from the head. It could represent a headdress of this design, but that seems rather less probable than its being a pictorial expression of a medicine path connecting the head (a place where the soul resides), with the celestial spirit abode. Even as a headdress, it probably retains the same symbolic significance.50 The second example is a Greek cross within a petaloid circle. Draped over the cross bar of the cross is what looks like downward spiraling drapery in a double helix pattern. The cross, like the more elaborated swastika, is typically a symbol of the center, the bars of the cross forming a kind of reticle that precisely defines a geometric center, the meeting point of the arms. The center defined by the arms of the cross also forms the center of two concentric circles that surround the cross. Outside these circles are what appear to be flower petals, the whole giving the impression of a sunflower. The result suggests a symbolic representation of the sun, here seen as the center of a vortex whence emanates the double helix that descends to earth in ever widening bands, as if in perspective. The double helix as a "medicine path," here emanating from what appears to be a symbolic representation of the sun, is similar in conception, albeit in a very different artistic style, to its counterparts at Gottschall.51 The petaloid circle containing a cross is widely distributed in Mississippian culture, where the cross is sometimes modified into a swastika, representing a rotating motion, rather like the solar-like object surmounting the head of Ghost at Gottschall.52

The third example is of a similar double helix rendered in a different artistic style, with sets of parallel lines in a more elegant counterpart to the Micmac pictograph above.53 In this gorget design, two men are facing one another and each is holding his own cauldron out of which the helices ascend. Each cauldron is shown as if it were transparent, the rotating lines curving together at the midpoint of each cauldron, and contained in this loop within each cauldron is a Greek cross. Therefore, the third example is something of an inversion of the second. The cross here marks the ritual Center (in Eliade's sense) here on earth, and the double helices ascending, represent the supernatural path by which the spiritual essence of the offering rises to the spirits above. This may function as a symbolic representation of the spiritual essence of the rising smoke or steam said to play the same role. The fourth example, which is broken at the top left, clearly depicts a ceremony of some kind, with one high ranking individual handing a cauldron off to another. Between them and beneath the cauldron stands a column decorated in a series of vertically ascending "targets" of three concentric black circles each. Emanating from the cauldron is a vertical double helix made up of four black lines separated by three white lines, which is the same as the "target" pattern on the supporting column. Although the left side is broken off, the right side is intact and appears to terminate in a wing tip. Just short of the wing tip is a slightly oval rattle striped with three white lines against a black field, the same pattern followed by the other aforementioned lines. A forked structure surmounts the top of the rattle, and below the oval is a handle.54 The double helix of this work of art looks very much like the Micmac design reoriented to the vertical axis. It would seem to represent a creative vortex which reëxpresses the metaphysical function of the column itself, whose "target" designs may also represent vortices as seen from above or below. In fact, the Lakota have the exact same "target" symbol which they identify as the kapemni vortex pair as seen from above.55 Since the double helix vortex emanates from the cauldron, it may represent the "spirit path" taken by the presumed offering contained in the cauldron. That the "targets" and the vertical helix may represent two perspectives on the same thing is reinforced by the large ceremonial ornaments worn by each of the men holding the cauldron. The one on the left appears to have attached to his back a swan or goose of about four feet in length, extending down from just below his shoulder to the back of his knee. The corresponding figure on the right has a large circular device, a more elaborate "target" of six black concentric circles, the last third of which is cut off to fit on his back. The outermost circle has a series of elaborate rays which have a zigzag pattern to them that point back to the center of the concentric circles. This gives it a solar appearance. It is of a piece with the other "targets" and the oval rattles in front of the double helices. All these may represent the sun as a creative vortex and the terminus of a spirit path (as the star is in the Micmac example above). The vertical path and its motion is captured in part by the swan or goose, which is a bird that traverses the vertical worlds and can therefore symbolize motion along this path. His head is pointed upward and his wings are spread, so he recalls the winged double helix above the cauldron and the column. The effect of the column, the double helix with its winged termination, recalls not only the water bird ornament, but the caduceus of Hermes, the wand of the divine messenger and herald of the gods who traverses the worlds in order to make communication among them possible. This is, indeed, the central purpose of an offering, to traverse these otherwise distinct and separate worlds in order to effect communication to their mutual benefit. The kilts of the two men in examples 3 & 4 are ornamented in different ways with the Greek cross, what the Hocągara called "the Earthmaker Cross." This may itself be a static representation of the Center also expressed by the target design. This would be similar to the swastika in its import.34 [For more remote parallels to the double helix, the caduceus, and the Hindu svastika, see Comparative Material below.]

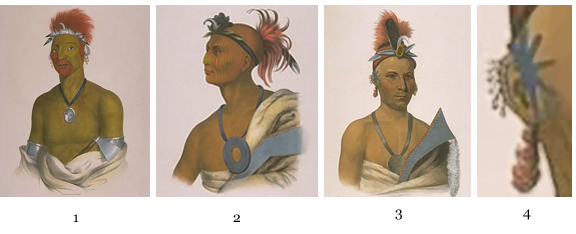

The Rayed Orbs. This double helix in the depictions of it in Panel 5 is not a forelock connected to the head, but in every case it is connected to the disc surmounted on the heads of three of the anthropomorphic figures. It has been suggested that this is a coronet or garland of some kind, perhaps on the model of that worn by the Thunders, who are said to wear a red cedar (waxšúc) garland on their otherwise bald heads. However, for historical models we should turn to the peoples who occupied this area from 1640-1735, before it was (re)occupied by the Hocągara. These are the Fox and Sauk nations, who are Algonquian speakers and therefore not related to the Hocągara or Chiwere peoples. Nevertheless, there was a great deal of commerce, not to exclude the commerce of ideas, among these tribes. For the rayed crown, we have an interesting example from this depiction of a Fox warrior by Lewis (Image 1):

However, what makes it somewhat unlikely that this is what was being depicted at Gottschall is the fact that the pictographic orbs are on edge in relation to a coronet. Nevertheless, the coronet might well symbolize the same sort of thing, if it is not just a decorative device. In the pictures above (Image 2) we have another Fox warrior, Tahcoloquoit, who not only has a coronet of a different sort, but has the Akron lines painted on his face very much like the sculpted head found at Gottschall. However, the most interesting example actually features the very orb under discussion (Images 3 and 4). It has been observed that the orbs on all the anthropomorphic figures have 7 rays, but there would be 8 if we extrapolated to the point where the orb rests against the crown of the head. In the portrait of the Fox chief Keesheswa, the disc with 8 rays is painted right next to his ear. It is probably a coincidence that this symbol is painted in the same blue-gray as the Gottschall paintings. It may not be a coincidence that the rayed orb is painted next to his ear. The ear is the organ of sound reception, and sound, because of its radiation in all directions from a center, is often a symbol of the cardinal points. Kings in the ancient Near East and elsewhere were said to be "Lords of the Four Quarters," a title bound up with the symbolism of sound and the ear. Since Keesheswa is a chief, this could be the import of putting this eight-rayed orb next to his ear. The brass ring, forward facing with a silvery hooked ray above it, does recall something of the rayed orbs shown in the Gottschall paintings. Nevertheless, in the paintings they are connected to double helices, which in the case of Ghost is itself connected to what is certainly an inverted bird. All this involves symbolism, so even if it were established that there were actual coronets or garlands of the sort seen in the Gottschall paintings, we are still left with the question of what their symbolism is in this context, a context in which one of them is not passive, but is involved intimately in the action taking place.

This disc, as it is surmounted on the head of Ghost and the other figures, is the source and terminus of the double helix, which is to say, supernatural power. The double helix is not the only thing emanating from the disc. Each disc is surrounded by rays. Such discs are found in pictographs of known meaning. In ISLan (Indian Sign Language), a disc formed by the index finger and thumb, as illustrated, denotes either the sun, moon, or star, depending upon which other signs are added. By itself, the sign means "sun"; if it is preceded by the sign for darkness (or night), it denotes the moon; if the sign is made and the index finger is flicked back and forth to indicate twinkling, then it denotes a star.35 Such unities are seen in the Hocąk language. The word wi by itself means "luminary," but without modification, it usually stands as an ellipsis for hąpwira, the day luminary or sun. Hąhewira, "night luminary," is the word for moon, although when -wira occurs in a calendrical context, it will denote "moon" or "month," as in Hųc-wi-ra, "the Bear Moon." Wi-ra gošge denotes stars. All three are luminaries (wi) in Hocąk. In ISLan, "sun" and "star" are represented by discs, and "moon" by a crescent.

In pictographic writing, the luminance of two of these are represented by rays, the moon being represented by a crescent. The disc on the head of Ghost has twisted rays suggesting a counterclockwise motion, whereas that of Flesh exhibits straight rays. The double helix emanating from Flesh's disc does not terminate with another figure, but the double helix of Ghost extends down a good distance and terminates in a picture of an inverted "black" (solid colored) bird. In later pictography, the practice of inverting a creature and giving it a solid color has a known meaning. There are numerous examples from the XIXᵀᴴ century, as we see in the panel below.

Often it is enough to turn an animal on its back to indicate that it is dead. A set of instructions on how to make a pictograph makes this abundantly clear: "Death of an animal is indicated by the animal being shown in an inverted position, viz., upside down. In case of a deer being shown by a set of deer horns, reverse the horns to represent death. Where a bear is shown by the bear's paw, reverse the paw with claws up to represent death."36 However, as we see from our examples, coloring it in and making it solid is another conventional way of representing the animal's death. The two figures at the end of the series of pictographs above, for instance, represent two dead people. So the inverted, solid colored depiction that we find in Panel 5 at the base of the Ghost figure would conventionally represent a dead bird, by attested pictographic values. We have seen that the double helix represents supernatural power, and it originates in the disc whose rays suggest spinning. The spinning disc represents either Ghost's own power as a stellar being, or his power as an expression of the sun, inasmuch as he is one of the Children of the Sun. So according to late pictographic conventions, what the depiction says is that "a man with solar/stellar connections, applied supernatural power to a bird, resulting in its death." This is what one widespread version of the Twins myth tells us happened: Ghost kicked to death a Thunderbird nestling, something that could be done only with immense supernatural power. Flesh, at this point, is not taking part, so his supernatural power is inactive, although present. It does not, therefore, terminate in a result. This inactivity is reinforced by the static depiction of the rayed disc, which shows no hint of action itself and his double helix does not come to ground in any object. When we examine the "apron" that Ghost wears beneath his oval gorget, we see that it is decorated in this same double helix motif. A series of such double helices are arranged in parallel vertical columns, and suggest in this design even more strongly the up/down directionality of the double helix. Its being surmounted, so to speak, by an oval disc, repeats the pattern of the solar-like discs that stand above and connected to the double helices that project down in front of the three humanoid figures. This is an artistic reenforcement of the theme of spiritual power that is particularly manifest and expressed in the figure of Ghost. It is absent in the figure of Flesh precisely because he is less powerful. [This subject is discussed further below under "The Seven Rays of the Orbs." For parallels to the rayed orbs or discs, see Comparative Material below.]

The Nestlings. The inset is a picture of the object being touched by Ghost's left hand, with an outline traced in red that suggests the form of a bird. This object is almost certainly a bird, and one a good deal smaller than the one to its right which has been identified as a Thunderbird. According to our stories, especially "The Lost Blanket" versions, there should be at least two nestlings whom the Twins confront. The pale green line traces the outline of what might be a stone, which is of interest since "The Lost Blanket" story says that the Twins fought the Thunderbirds with stones.  The filaments that seem to extrude from the bird's outline might be either a representation of down feathers, or biological effluvia ejected from the impact of Ghost's left hand thrust into the center of its body with, as the green outline suggests, a rock. However, it is almost certainly the former, since Panel 3 shows what is clearly a bison whose hair is rendered in this same manner.37 While "The Lost Blanket" story does not at first describe the fate of the nestlings, later on (as we shall see below) it states that they were killed by the Twins and made into headdresses. So the painting here is interpreted with no difficulty as Ghost killing two nestling Thunderbirds in succession, the first of which lies at his feet and the second of which is seen in the very course of its destruction. It may be that the young bird is merely being gripped by Ghost's left hand, but it would not be surprising if that Twin had executed the coup de grave from that side. There is more than one reason to think so. Striking a mortal blow with the left hand would demonstrate unusual power, since normally the left is the weaker side. As to flesh and spirit, we might expect flesh to be associated with the right, the familiar world, and the ghost to be associated with the left, the world of death and the Beyond. Also, given the moral priority of right as the "correct" hand to use in almost everything, the use of the left hand to commit an act of deicide seems very appropriate to one of the central messages of the Twins Cycle: that the supreme power given the Twins caused them to lose their moral constraints and to cross the boundary of right action into the realm of excess and moral error. The assault on the Thunderbirds was not why the spirits in general gave of their collective powers to create these beings of incomparable might, it was to do the opposite, to restore the balance of the universe and set things right. The Twins in their excess have gone Left when they should have gone Right. This reason for why the left hand leads the assault against the Divine Ones is reinforced by a similar inversion. A reexamination of the solar-like disk above the head of Ghost suggests by the forward curvatures of its rays, a counterclockwise motion. Conventionally, as we have seen, the ISLan sign for holiness or medicine describes the double helix of supernatural power as rotating clockwise. Inasmuch as the double helix is attached to a source that seems to be rotating the opposite direction, the helix can be presumed to be rotating to the left as well. If this is correct, it asserts that Ghost's supernatural power is bad medicine used in a counterproductive cause. Therefore, the projection of the left spinning double helix from its holy source on to the prostrate bird below is just another image of Ghost's left handed assault on the second nestling. The reduplication of narrative motifs is a cornerstone of mythology, and we see the same principle being applied in the pictographic representation of the present myth.

The filaments that seem to extrude from the bird's outline might be either a representation of down feathers, or biological effluvia ejected from the impact of Ghost's left hand thrust into the center of its body with, as the green outline suggests, a rock. However, it is almost certainly the former, since Panel 3 shows what is clearly a bison whose hair is rendered in this same manner.37 While "The Lost Blanket" story does not at first describe the fate of the nestlings, later on (as we shall see below) it states that they were killed by the Twins and made into headdresses. So the painting here is interpreted with no difficulty as Ghost killing two nestling Thunderbirds in succession, the first of which lies at his feet and the second of which is seen in the very course of its destruction. It may be that the young bird is merely being gripped by Ghost's left hand, but it would not be surprising if that Twin had executed the coup de grave from that side. There is more than one reason to think so. Striking a mortal blow with the left hand would demonstrate unusual power, since normally the left is the weaker side. As to flesh and spirit, we might expect flesh to be associated with the right, the familiar world, and the ghost to be associated with the left, the world of death and the Beyond. Also, given the moral priority of right as the "correct" hand to use in almost everything, the use of the left hand to commit an act of deicide seems very appropriate to one of the central messages of the Twins Cycle: that the supreme power given the Twins caused them to lose their moral constraints and to cross the boundary of right action into the realm of excess and moral error. The assault on the Thunderbirds was not why the spirits in general gave of their collective powers to create these beings of incomparable might, it was to do the opposite, to restore the balance of the universe and set things right. The Twins in their excess have gone Left when they should have gone Right. This reason for why the left hand leads the assault against the Divine Ones is reinforced by a similar inversion. A reexamination of the solar-like disk above the head of Ghost suggests by the forward curvatures of its rays, a counterclockwise motion. Conventionally, as we have seen, the ISLan sign for holiness or medicine describes the double helix of supernatural power as rotating clockwise. Inasmuch as the double helix is attached to a source that seems to be rotating the opposite direction, the helix can be presumed to be rotating to the left as well. If this is correct, it asserts that Ghost's supernatural power is bad medicine used in a counterproductive cause. Therefore, the projection of the left spinning double helix from its holy source on to the prostrate bird below is just another image of Ghost's left handed assault on the second nestling. The reduplication of narrative motifs is a cornerstone of mythology, and we see the same principle being applied in the pictographic representation of the present myth.

Another odd thing about these nestlings is that they have no feet. They could hardly be designed that way by nature. (The large Thunderbird is the same way, but that may be because the rock surface ran out before the feet were reached. On the other hand, it could have just been painted slightly higher up and depiction of the feet would have been possible.) Surely the lack of feet has some significance, but what could it be? Once again we can turn to recent plains pictography to get an interesting solution. There is a picture of a Dakota taking captive a Crow man and woman. It is a minimalist composition, practically a group of stick figures, except that the woman is identified by two round circles indicating her breasts. The woman is to the left of the captor, and the man is to the right. Also shown are the hands of the Dakota, but the hands of the prisoners are missing. Col. Mallery explains, "[The pictograph] shows a Dakota method of recording the taking of prisoners. ... It is noted that the prisoners are without hands, to signify their helplessness."38 This same symbolism seems likely to be operating in the Gottschall exemplars. Since birds use their feet for grasping, they become the counterpart to human hands. The nestlings, and perhaps even Great Black Hawk himself, are helpless in the face of the immense power wielded by the Twins. To show this, their "hands" (talons) have been removed, indicating that the organs of executive power have ceased to function.

Great Black Hawk. In the inset, the picture of the large bird in Panel 5 has been isolated with the trailing human figure removed. The bar found across the face of this latter personage extends all the way to the avian figure, and therefore may be a part of it.  Therefore, in this isolated view, I have left it attached as though it were. Accepting provisionally the hypothesis that this is a Thunderbird, mainly on the evidence of the forked pattern emanating from the eyes, can the addition of the "bar" add anything to our interpretation? Its situation is at the back end of the bird right next and above the part that seems to represent the tail feathers. It is hard to see it, therefore, as anything other than a tail itself, in the raised position that it usually assumes when a raptor lands with a braking action. When interpreted this way, it becomes, in conjunction with the other section also interpreted as a tail, a dual or "forked" tail. Such tails are found on a number of highly aerobatic species. Thunderbirds assume the somatic form of various species of birds. Their chief, Great Black Hawk, has the bodily form of a black hawk when he wishes to be in an avian modality. We must assume, for instance, that Little Pigeon Hawk, who is also a Thunderbird, must likewise have the avian form of the species recognized in his name.39 So on what kind of a bird is the body of the large Thunderbird in Panel 5 modeled? The aforementioned tale "The Lost Blanket," gives an epilogue to the fight between the Twins and the Thunderbirds which supplies us with a good idea of what bird might be depicted here. The story relates how Ghost and Flesh climbed a hill and looking down espied a very large village.